Artworks

Installations

“Everything in the world is beautiful, but Man [sic] only recognizes beauty if he sees it either seldom or from afar. Listen, today we are gods! Our blue shadows are enormous! We move in a gigantic, joyful world!”

Vladimir Nabakov, Gods, 1923.

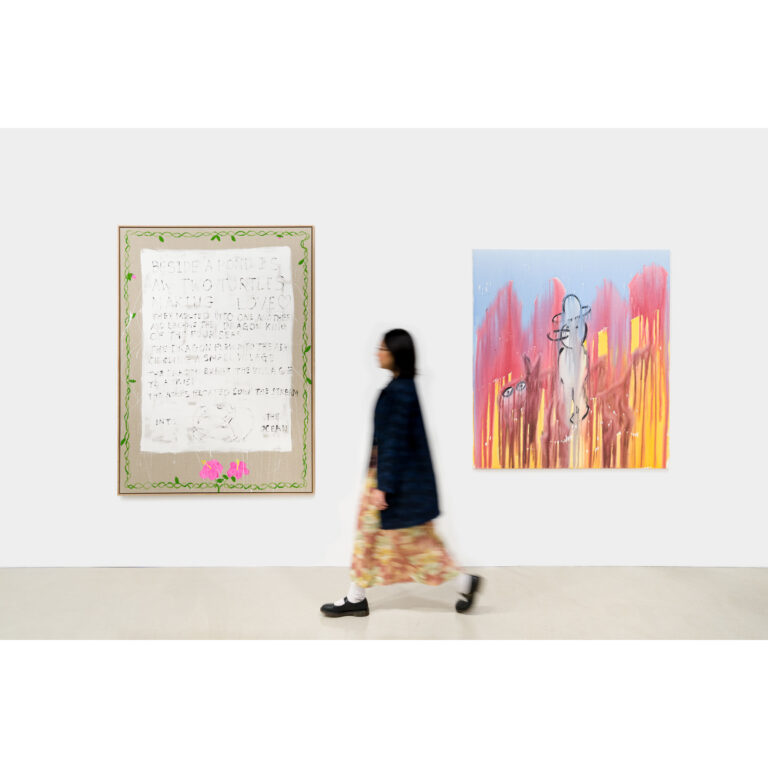

Chalk Horse, in close collaboration with their stable of artists, has made an exhibition set in Nature, filled with spirituality, magic and wonder. What unifies this exhibition is faith that art can return to beauty without irony and that large abstract concepts (like love and spiritual life) are still subjects for art. The scare quotes of postmodernism have been replaced by a new sincerity.

Art and Nature have traditionally been thought together in Western aesthetics as two categories that can be experienced as beautiful. After the postmodern, in a post-humanist world, we can no longer rely on canonical certainties. The twentieth century separated art from beauty; Nature became a mythological state, and the beautiful itself became an incredulous term.

The contemporary revival of the Romantic, what Timotheus Vermeulen and Robin van den Akker identify as Neo-Romanticism, in their article ‘Notes on Metamodernism,’ is a marker of our current age that wants to reengage with the ethical and the aesthetic on so many issues facing the world. A number of writers have been thinking similar things.

Arthur Danto, following provocations by David Hickey, pointed out, beauty is now an aesthetic choice, not the definitional be-all and end-all of art. In On Beauty 2002, Danto writes:

Beauty is one mode among many through which thoughts are presented in art to human sensibility – disgust, horror, sublimity, and sexuality are still others. These modes explain the relevance of art to human existence, and room for them all must be found in an adequate definition of art.

The artists in this exhibition have chosen beauty as a useful tool in their work and accessed a variety of approaches.

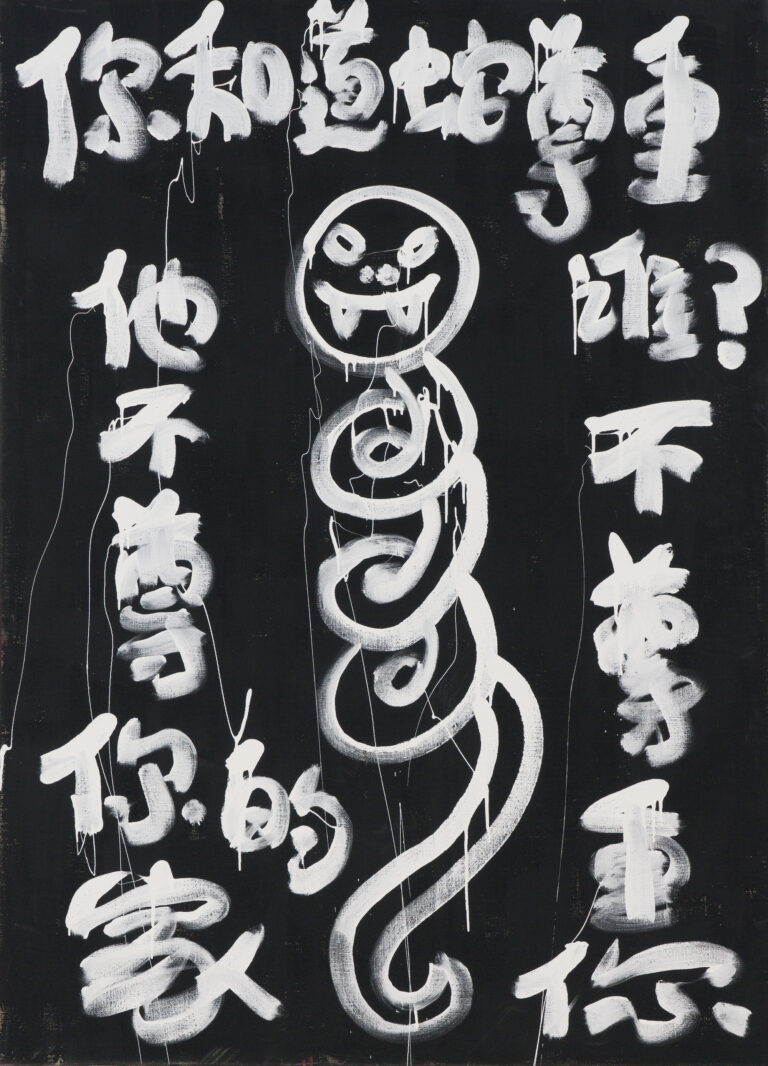

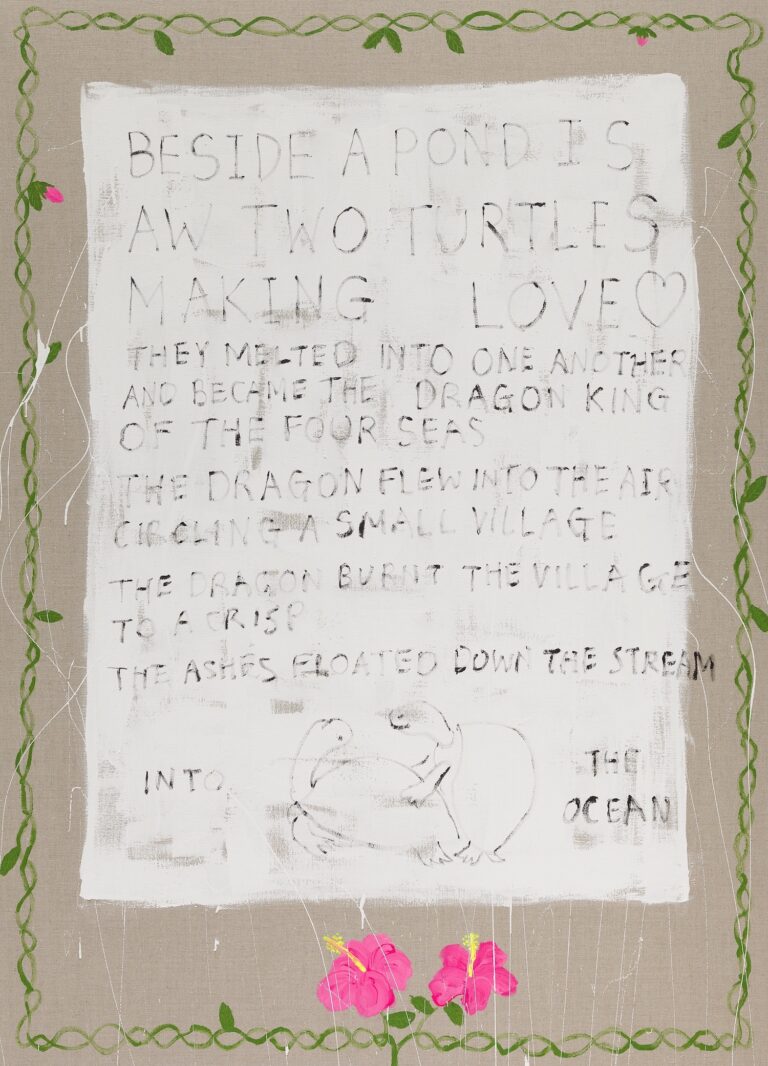

Starting with Jason Phu’s cowboy, we can see the heroic categories have been declassed. Hard masculinity turns into a pool of paint/blood on the ground. But copulating (erotic?) turtles and scary snake demons are not just cartoon sketches. They point to the most important existential questions of the viewer. Phu draws us in with floral borders and cuteness, but the aftertaste is long and complex.

Both Mechelle Bounpraseuth and Kate Mitchell extend this approach. Like good Symbolist or Imagist poets (think Redon and Oscar Wilde), they have found the universal and sublime within the everyday. This approach returns in the contemporary moment because instead of talking for everyone, beauty’s universalism is contradictorily linked to singularity and difference.

Instead of relying on traditional gods, Mitchell finds spirituality in all her daily activities and meditations. Philip Fischer, in his book Wonder, the Rainbow, and the Aesthetics of Rare Experiences, best sums up this turn to beauty as a smaller, more individual but still shared experience . Like sacred silk miniatures, Mitchell conflates the highest and lowest, from the shimmering moon to the smelly garbage can, and finds beauty and hope everywhere.

If much of modern painting played on the borders of abstraction and figuration, Clayton Smith really pushes the lever down on the abstracted and transformed. If the process of painting for Clayton Smith could be put into theological terms, it would be Via Negativa. It is the hermetic process of saints that strip down, pull back and simplify to find the truth. The thin veils of paint have become even more calligraphic and sure. The wiping back and erasure, more focused and direct.

Bounpraseuth’s slightly sad-looking pot plant created in everlasting and ancient ceramic, becomes a metaphor for life and death and the struggles of a lack of resources and sustenance. Even here, one senses the promise of a good watering. Alex Standen similarly draws on the ancient crooked will of the ceramic form. Her vessels shine and glow like a vessel from a cathedral altarpiece. Only here, the pearlescent lustre is from her own sense of the spiritual, made for a corner of anyone’s home.

So even though beauty is not the immense philosophical category it once was, all these works show that its legacy still functions. There is an ethical and aesthetic component to finding beauty in the world and reproducing it in art.

Some artists in the show have leant into the long history, the deep tendrils of art history, made old symbols fresh again and renewed them for a contemporary world which may be a little more doubtful and uncertain. Instead of the palms of, say, the Songs of Solomon, Jasper Knight captures the mystical uncertainty of Centennial Park heightened by a silvery twilight light. Instead of the sublime of Nature, Oliver Watts presents two lonely trees in a storm at 1 Bligh Street, an office-bound sublime; his wild dog, although a scene he saw, was modelled by a friend’s pet. Dean Brown elegantly expresses, in controlled gestures, the loneliness of the stranger in the city. Danny Morse shows the ancient poplar, long a European symbol of death and remembrance, rising almost surreally from the Australian plain. This image shows the complexity of image-making in a post-humanist vein, which must still rely on the past while looking squarely up the complexities of the present.

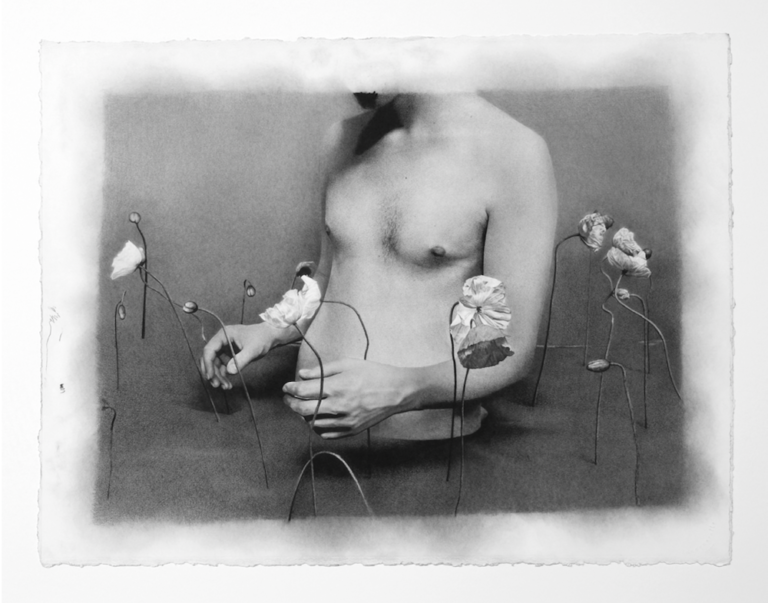

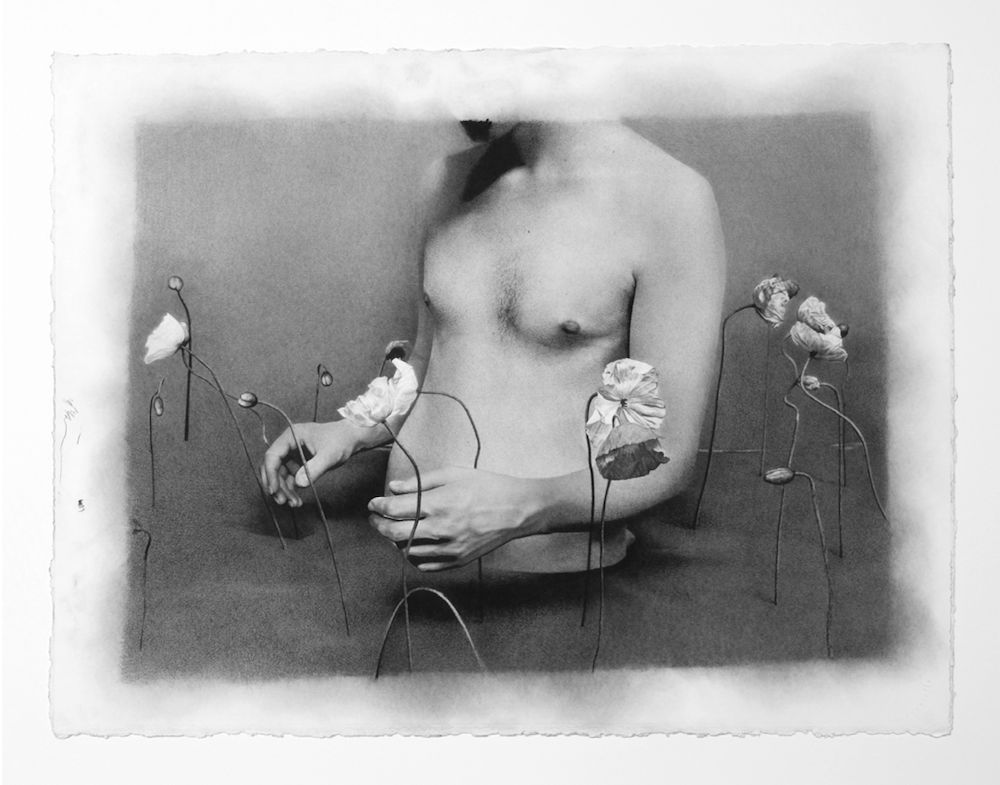

In the work of Harley Ives and Harry McAlpine this playing with time reaches its most complex point. McAlpine draws on the poppy, the flower of dreams par excellence. The image is strange, collaged, and suited well to our digital universe of cuts and snatches. There is a quietness and solemnity to the final image, redrawn slowly and carefully. Harley Ives, on the opposite spectrum, animates the image through digital video bringing flowers to life in a floral hyperbole, the essence of flowers condensed and repackaged. It is a work of energy and vibrancy.

Overall the works have a slightly gothic feel. There is a little darkness and tension in all of them. This is the artists really wrestling with the seriousness of their mission. They are all, for the sake of the viewer, trying to squeeze meaning out of traditional concepts (of beauty and ethics, of love and the spiritual) in a world that does not always wish to support fundamental values or even to make time for contemplating the flower in front of our nose.

Oliver Watts, 2023