As is expected from Danny Morse’s work this exhibition is full of wit and conceptual complexity. It is an exploration of a theme over a tight and considered body of work. The bedrock of the exhibition is the river stone, often sourced from a family property in Northern NSW. Out walking across the smooth stones of the creek, which is on the property, he has sourced the ones he thinks are special.

Morse has often used found objects before in his work, whether presented as is or in some way altered. It is a technique that was brought to modernism through the surrealist “objet trouve” and was supposed to be a real thing that through its strangeness or “marvelousness” pierced the everyday drudgery of life and pointed to another zone of possibility, “the surreal.” For Breton and Man Ray and the others a specific weird spoon, an ad for Mazda cars, a mask or anything really could potentially become through nomination a surreal object.

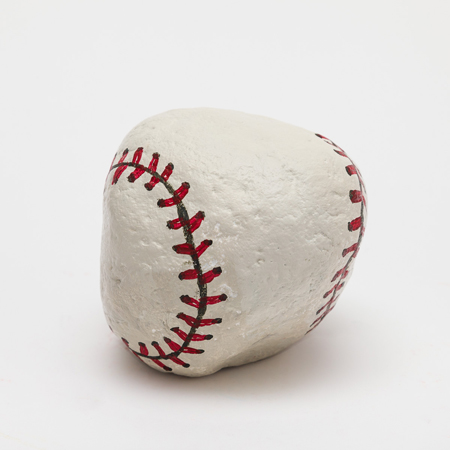

For the surrealists though the object was rarely natural, although vine covered ruins often got a Guernsey. Here the rock also harks back to an older mythology. Is the finding of the rocks a really earnest exercise, attentive to the actual shape and quality of these things, not strange but in a certain way beautiful and perfect. The highest form of such aesthetic taste is the Japanese Suiseki, or the Chinese scholar rocks, Gongshi; in these cases the traditions elevated the choosing of rocks so highly that they have become an art form in their own right, in an art that has no direct equivalent for Western art. The stone for the scholar monk could remind them of a mountain, or a cloud or a thatched pavilion or an animal. These rocks, sitting proudly in a garden or on a desk became the basis of reverie or meditation. Is it so strange that Morse, living in the West, in our contemporary age happens to see a baseball in a stone?

The neo-Romantic art of the conceptualist Richard Long also involved in part sourcing and placing rocks in the gallery. The formal intervention was minimal, placing the rocks in a line or in a circle or as a cairn, but it was enough to sign that the rocks had become art in some way. Ugo Rondinone recently has painted and stacked stones.

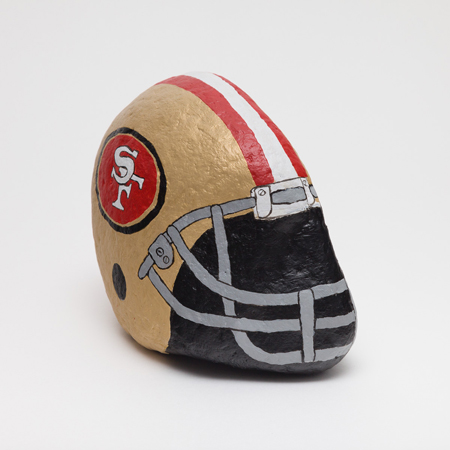

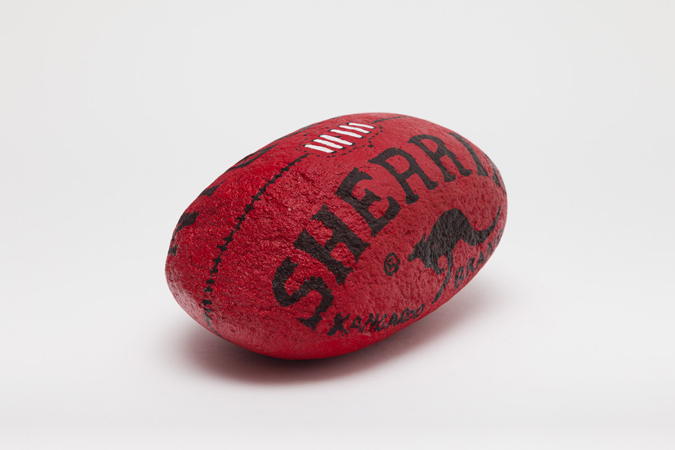

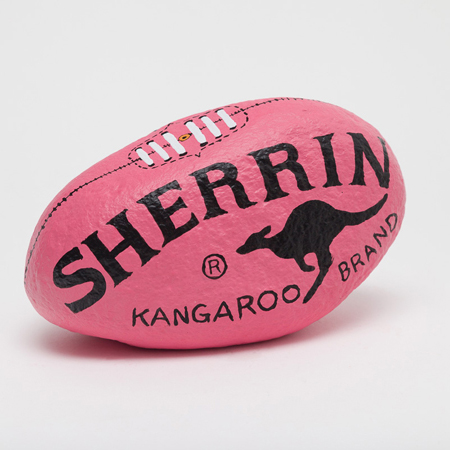

Morse’s work seems to play on the borders of all these approaches lurching between the serious and the camp, between the beautiful and the kitsch. It is this ambivalence that makes these works striking and contemporary. There is a clear humour here too. Every title puns on the rockiness: rocks like boxing gloves become Rocky I and Rocky II (the famous sequel); the pink football becomes Sherrin Stone; Roundball Rock is the NBC television theme song for the NBA in the 1990’s.

Even Morse’s transformation of the rocks into balls is obsessive and well observed. The baseball clearly has its double stitching, the basketball has acrylic dots as grip on its surface, the logos are lovingly recreated. It is an obsessive remaking almost to the point of the absurd. The time and effort to make something so banal is a refusal of the fast time and incessant purposefulness of contemporary life, almost as meditative as walking in the wilderness looking at rocks.

What is astounding is after all the paint the rocks still assert their weight. In the basketballs the weight of the rock seems to squash the balls as if mid bounce, or as air escapes. Then you think of the stones themselves, smoothed over time through water, grit and gravity to take on the round shapes that Morse has so celebrated here. The quickness of our human games and sport seem to disappear in the long time of geological processes. The planet, the earth and the rocks reassert themselves. The work shows that we can no longer rely on the older Romantic myths for our relationship to nature (the scholar monk, the gentleman on his walk, or even the wilderness), there is no natural artefact that isn’t already placed under the human hand.

Oliver Watts