Chalk Horse presents an exploratory exhibition on the nexus of art and law. Tim Gregory, Janet Chan, and Oliver Watts all lecture, study and research, in one way or another at the University of New South Wales. On realising their shared interest in visual culture and the law they decided to mount this exhibition. As part of this collegiate spirit Gregory and Watts will reprise their role as co-lecturers to expand on the exhibition at the opening through a lecture/performance/opening statement.

This exhibition is more than imaging the law. All three artists ask questions about law and the image broadly. For example does the law have a gaze, how does the law see? Isn’t it blind? Does the law use images to legitimise its position? Or on the other hand does art history have a slew of images that command and authorise? Do you bow down in front of an image? And from an even greater distance can aesthetics and art help us understand the limits of the law? Can it reveal the way we are interpellated by the law, the way the law and image conspire to create a community that can define and defend itself? Does this relationship even shape how we know what to desire, what desires are allowed to be visible and which need to remain hidden.

Tim Gregory continues this theme arguing that the law and the image are in an incestuous relationship with each other. Through incest the law and the image seek to double their legitimacy in the same way the pharaoh brother/sister, King/Queens did. Justice may be blind, but only to itself (and as a result of too much inbreeding). It is vital we see justice as a bound and vulnerable woman. In this way taboo desire is the proper partner to the law, although they must never been seen together. In Gregory’s series ‘Sext 78A’ he outs this relationship by becoming the paparazzi to his own taboo image. He snaps some pictures and asks what happens when Greg (Barry Williams) and Marcia (Maureen McCormick) are caught kissing on the lot?

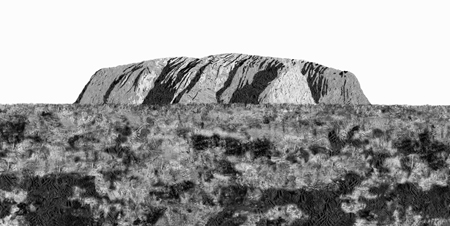

Janet Chan’s work plays with many registers from the indexical (footprints, finger prints), the metaphoric (layered evidence as the layers of rock in mountains) and traditional iconography (sites of crime, mountains as places of beauty and scholarly refuge). Chan uses her experience as a criminologist to plumb the law’s surveillance and the forensic images that are created. Using digital techniques Chan moves seamlessly between these various registers. Chan’s work calls to mind shows like CSI that turn forensic science into sublime imagery. Chan demonstrates that evidence does indeed build a picture, and that the final judgement, in channel Nine’s ratings and in the courtroom, is based on the aesthetics of that picture. Judges and juries have become art critics.

Oliver Watts revisits a fairy tale about a princess and a mythical sea-hare form the Brothers Grimm and a story that David Hockney also imaged. As in the work of Gregory, Watts shows that the law is desirable and desirous and not so cold. The princess is the sovereign ruler with the power of life or death but it doesn’t stop the story beginning with 97 heads on pikes of previous suitors that have failed. Through videos and collage Watts illustrates/obfuscates the story through a variety of methods from jokes to critical theory.