Artworks

Installations

Where innocent bright-eyed daisies are,

With blades of grass between,

Each daisy stands up like a star

Out of a sky of green.

Christina Rossetti

In Mt Wilson, on Church Lane, past Withycombe, Sefton Cottage and Sefton Hall, past Farcry, and Dunarque, you get to the gates of Lane’s End. Having driven through an almost architectural canopy of trees that line the lane, with well established gardens on either side, Lane’s End opens up to the sky again, just an empty flat field. It is the far western border of Mt Wilson and facing west, the days always seem a little longer.

On the hand painted enamel sign next to the Post Office, the one the late Libby Raines painted in 1994, Lane’s End is called Wulla Wulla Gum Gum. This was the closest some previous owner could come, via a Disney character Witch doctor, to impart some sort of Indigenous authenticity onto the land. Although Mt Wilson has accepted the recent name change, still, if you type into Google Maps, 32 Church Lane, it autocorrects to Wulla Wulla Gum Gum. Somewhere in the Land Titles Office, or on a cartographer’s official map, the name is still hard wired. In the recent fires, and in the fires before that in 2016, the field was used as a kind of break for the more important heritage listed houses. The fire trucks, having smashed down the rickety gate to get in, parked on the field as the first line of defence. At least one bomb of fire retardant was airdropped along the perimeter fence in 2019 and turned a lot of the foliage flouro pink for a few weeks. Although the holes in the polyvinyl trampoline registered some ember strikes the house was not lost and perhaps more importantly Dennarque, 1879, was never put in immediate danger.

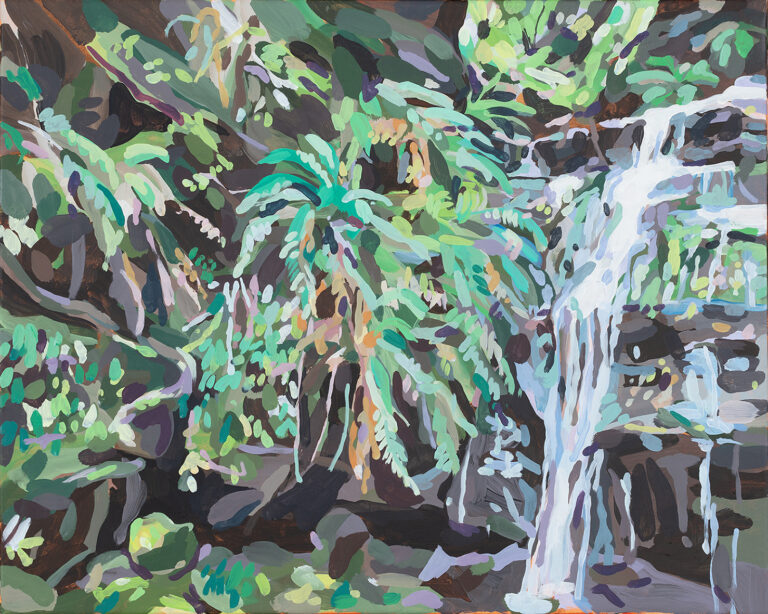

Originally the field was the less important bit of the Dennarque Estate. It was cleared first for an apple orchard and the cabin was apparently the apple barn. At some point that got cut down and the field was used to graze horses; you still occasionally find horseshoes. In August daffodils and jonquils grow neatly in phantom beds of some building that now only vaguely exists on a hand drawn watercolour diagram. Another strange feature would be the tree ferns, so high that people mistake them for palms, sticking straight out of the field with no other trees for company. Clearly through all its various uses the ferns were coveted enough to keep; the Victorian Era especially was crazy about them. Lane’s End is known locally as the fern place, because it has a large southern gully filled with tree ferns.

The three Bunya Pines, native but native to Queensland, are so big that they must have been planted near to 1880 as part of the original plan. Only the large gum trees would be older. The English walnut tree is a little younger and is the only one having lost touch with the rest of the nuttery in the partition.

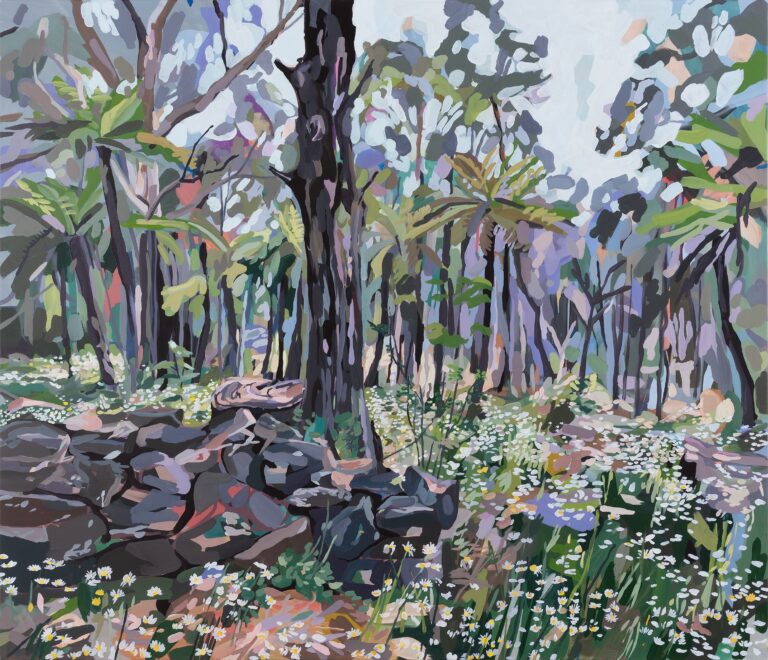

The field is now just a field and open for anyone to give it whatever meaning or playful use they want. In November, if it hasn’t been mowed, the daisies pop up in a huge horizontal plane of white. Butterflies and flies fly perceptibly above it. With a smattering of yellow dandelions the whole thing feels very dreamy and cinematic. If it weren’t for the Australian trees framing the scene, the meadow could be anywhere.

When the field is mowed it presents as a kind of lawn that in keeping with British garden design is surrounded by the “wild” of a forest. You are constantly reminded that you are on the edge of a real vast forest not just a gardened clump of trees. You hear it as the wind picks up sound through kilometres of rustling leaves. In fact, after the fires, it was the relative silence of the forest that hit you first.

One time looking out over the field a long black feral dog chased a grey wallaby all along the length of the grass until they both jumped the fence back into the National Park. It was a rare enough occurrence to log it with the rangers. On another occasion a two metre red belly black snake appeared almost magically within a metre of the small boys under the Walnut before turning totally back onto itself to retreat carefully as two parallel lines.

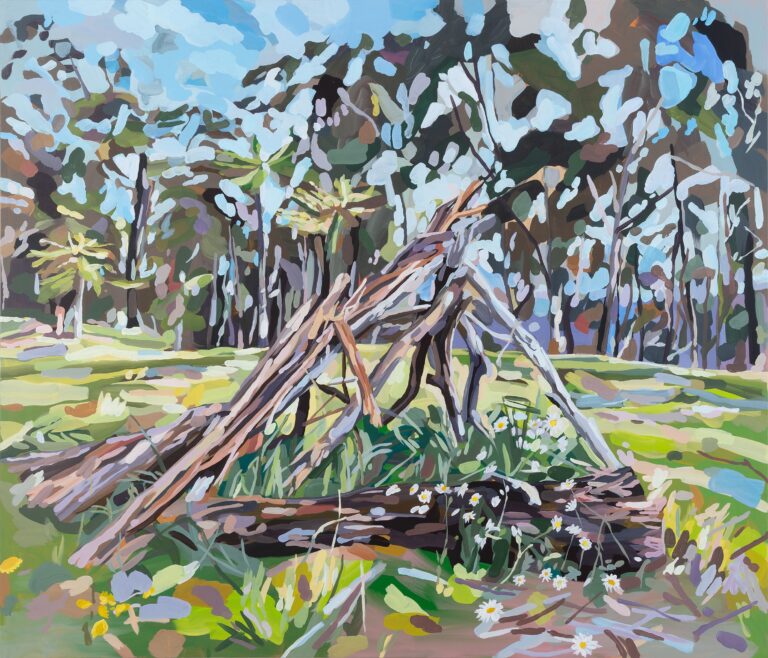

This year in an effort to properly engage with the bush and to let it in we agreed to cut down almost forty large radiata pines that were part of a very old windbreak and boundary marker. Once planting pines was considered good stewardship and the proper neighbourly thing to do. Now the pine is considered an environmental weed. Among other things the acidity of the fallen needles stop native trees regenerating.

The trees really had to come down urgently because the fire killed them, unlike the Australian trees that had their own systems. We found out recently from the Rural Fire Service that the boundary pines did indeed do their Edwardian duty, sacrificing themselves to stop the fire moving across the field. There is no pine tree wall to rely on but instead a new set of coordinates.

Oliver Watts, 2022