Artworks

Installations

When I googled Echo Point the first result I got was a karaoke bar by that name in Sydney. Not the harbourside strip of bushland at Roseville Chase where Danny Morse grew up and where he continues to live and work today. I hadn’t thought about karaoke in relation to Danny Morse before but now I can’t shake off the idea that somehow karaoke is exactly what his work is all about. Morse echoes things that have childhood resonance – cricket bats, watermelon, a balancing bird, Saxa Salt – so that they inhabit his voice and personality.

Morse spent much of his childhood at Echo Point as it is where his grandparents lived. He refers to the works comprising this exhibition as ‘sculptural sketches’, an ‘echo’ to a past that is singular to his own experience, but one that is generationally shared through nostalgia. Nostalgia is a conflicted concept. In a widely quoted scene from Mad Men, Don Draper refers to nostalgia as “the pain from an old wound – a twinge in your heart far more powerful than memory alone”. Morse is less inclined towards a romantic conception of nostalgia, leaning more towards cheeky absurdism, asking us to look at familiar objects plucked from consumer and popular culture through his idiosyncratic lens.

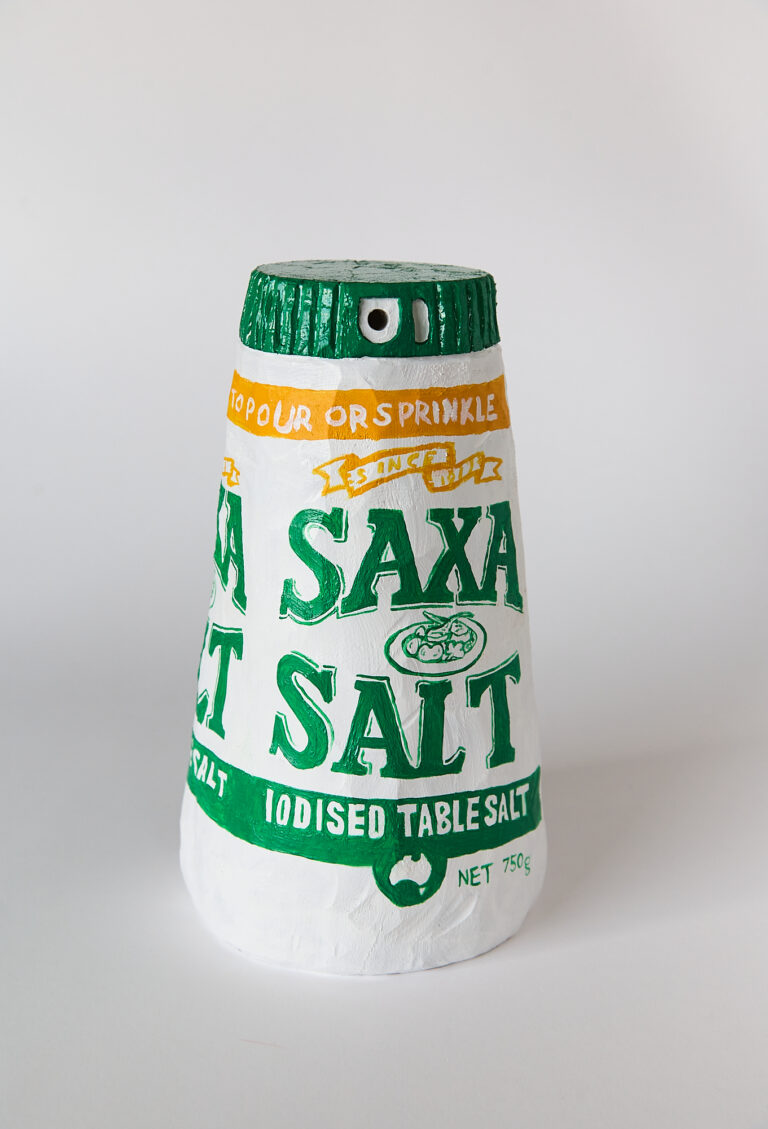

Morse is a trickster with materials. When a storm wreaked havoc on Echo Point, Morse salvaged the wood from felled trees left by the State Emergency Services. Turning wood into salt is amusing proof of Morse’s ironic alchemy of natural materials sourced from the earth. I’m reminded of Lot’s wife, the Old Testament figure who looked back on Sodom as it perished at God’s hand. Zapped into a pillar of salt as punishment for returning her gaze on the doomed town, Morse’s inclination to ‘look back’ echoes this dramatic tale. At Morse’s hand, Lot’s wife is finally given a name: Saxa. The pillar she now inhabits is the iconic 1960s 750g drum, a mainstay of childhood memories of suburban picnics and sausage sizzles.

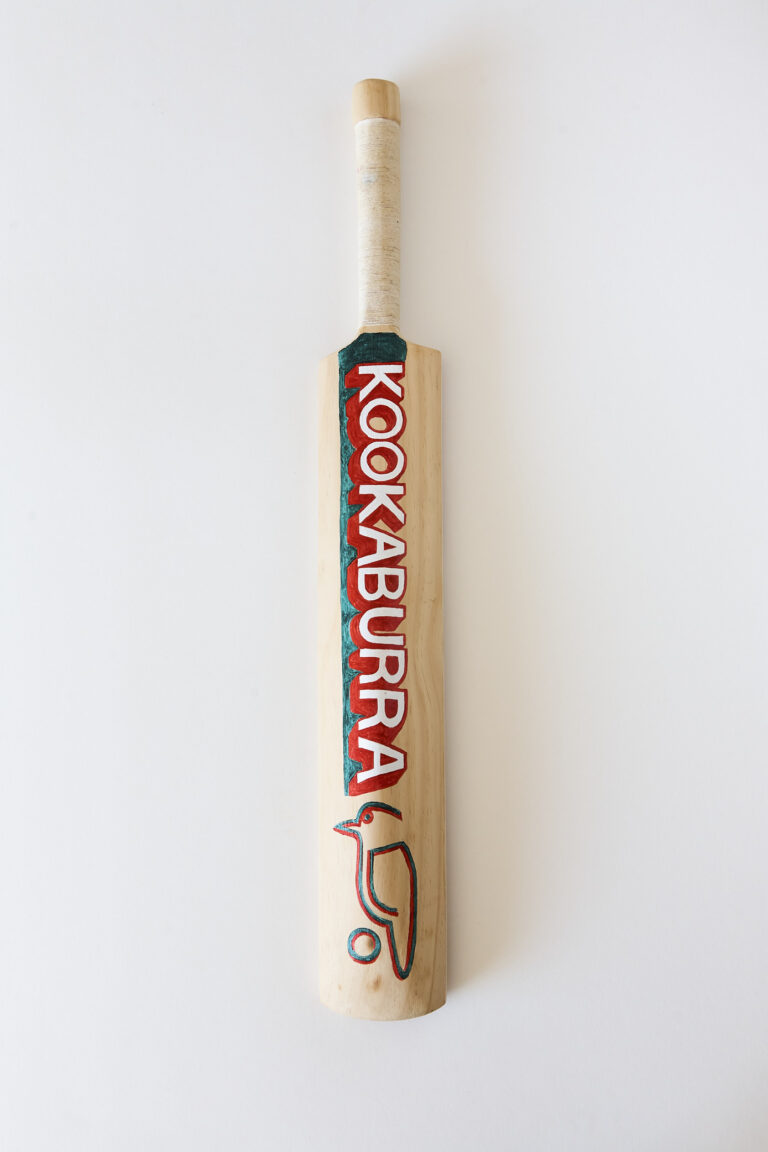

It goes without saying that evidence of the human hand is obscured through the factory production of mass consumer goods like table salt dispensers and cricket bats. As in the tradition of folk art, Morse shapes these things into sculptures that have their own aura and bear the trace of his hand. The resemblance to the referent is loosely approximated rather than painstakingly simulated.

Morse makes art pretty much the same way he performs as a Dad. It doesn’t take a stretch of the imagination to envisage Morse tinkering away in his outdoor bush studio, making his son a wobbly replica of the Gray-Nicolls cricket bat he had as a kid, because he can imbue it with much more fatherly love than what is possible from the store bought kind. Why buy a juicy watermelon from the market when you can make one from wood!

That’s what I love about Morse: the old-timey love he has for the quotidian, the sardonic joy he finds in the past, the way he packs a punchline. While an echo travels through space, bouncing off the walls, for Morse it is a static object frozen in time. An echo standing still.

Daniel Mudie Cunningham, 2020