The ‘blank’ force of Dada was very salutary. It told you “don’t forget you are not quite as blank as you think you are!” Duchamp

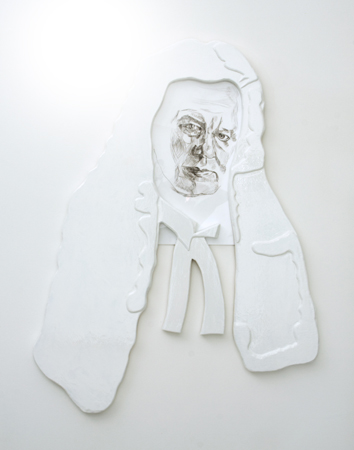

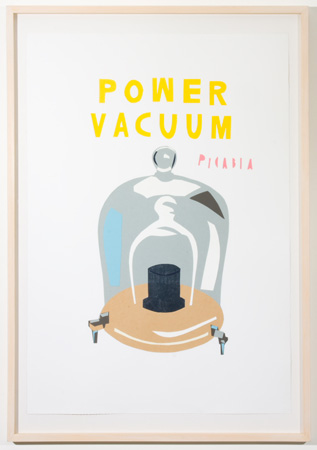

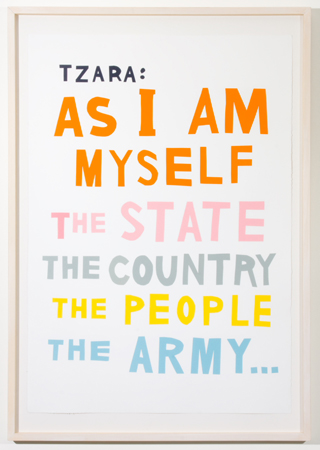

In 1921 the Dadaists held a mock trial slash cabaret performance. They used the court to fictitiously pass judgement on a writer who they thought had become too conservative and a traitor to their cause, Maurice Barrès. Barrès himself did not turn up but was represented in effigio by a shop mannequin. Breton served as presiding judge, and in a very un-Dadaist manoeuvre took the trial incredibly seriously. On the other side, Picabia absented himself and Tristan Tzara refused to be called to the Bar as an advocate or judge on the grounds that “I have no confidence in justice, even if this justice is made by Dada.” He only took part as an aggressive Dadaist witness who finished his testimony with a Dada song, embodying the spirit of revolt. Watts’ show and animation relate to this testimony.

The difference in perspective between the two parties can be seen in David Fincher’s movie Fight Club. At its end the schizoid Tyler Durden/Narrator character blows up the skyline as the culmination of his Project Mayhem. Why were the buildings blown up? The answer is ambiguous, and reflects the unresolved battle in the film (and Chuck Palahniuk’s book) between the anarchist Tyler, who would blow them up for the sheer joy of destruction, and the idealist Narrator, who would destroy them as a means of overthrow capitalism in favour of a morally superior alternative. In the film especially, it is left up to the audience to decide which character they side with most, the nothingness of random destruction or the beautiful vision of redemptive violence. The destructive nihilism of Dada similarly had two sides. Some, like Tzara and Picabia, were nihilists. Breton and the others would end up as communists and surrealists. The two faction came to a head in 1921.

For Tzara, the accused and the accusers were “a bunch of bastards… greater or lesser bastards is of no importance.” This anomic attitude, the questioning of what lies outside the law which also forms the basis of Kafka’s The Trial, is a pressing question to ask. And it resonates in our age of terrors and kingly presidents. For Tzara it was only in carnival, play and poetry that a place could be found from which you could critique the law and society. Tzara believed only in himself, in an anarchic individualism with no connection to social prohibitions. Watts has emulated this playful spirit to question the limit of the law with work that is part legal treatise and, part South Park. And Trey Parker and Matt Stone’s cartoon, of course, also alternates between criticizing the world as it is and rejoicing in sheer anarchic destruction.

The Dada trial ended in the dissolution of the Dada movement because Breton refused to endorse such a complete disavowal of the social conscience. The trial of Barrès reminds us of with what difficulty we define ideas such as freedom and individualism, and the tension between the demands of the law and individual liberty.