The paitings in this exhibition are testament to the unique and multi-layered works that are emerging from the Yinjaa Barni Art. The works are informed by the colours, elements and knowledge of the county around the Pilbara area where the artists live, and their interlaced and near-palimpsest layers of colour, tone, pattern and structure found in the paintings are ultimately those found in the layers of perception. vision and shared understanding of the land. Ultimately the earth and canvas can be read as one – Maudie Jerrold speaks of:

‘The massive colours of the county the land spread out through the whole region of the country areas, and creating colours of coloured shadowy figures of huge landscape, leaving many coats of colours, like the hill-top mountains, rivers, thick bush land and the land that forms the colours of the country.’

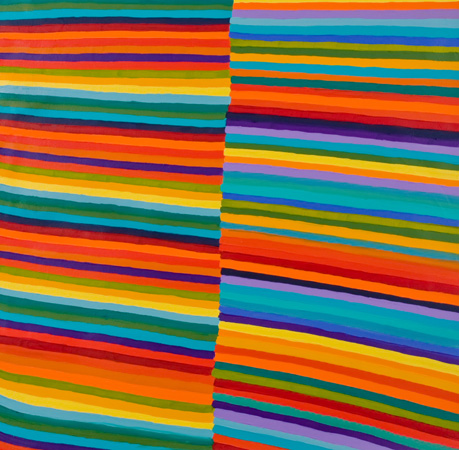

So too in Clifton Mack’s ‘Line Erosion’, the lines cutting through the fracture of the work as an interruption into the rolling refrains which span the canvas surface are taken from Yindjibarndi country Millstream (Jirndaiuurrna). The colours used to represent this ancient cut are the same ochre and white used by the Yindjibarndi tribe for corroboree – to paint on artifacts and for painting the country. In this way we see how in works like these, nature and culture (field and text) do not exist in a relationship of the latter laid on top of the former, but are impossible to unravel into discrete planes.

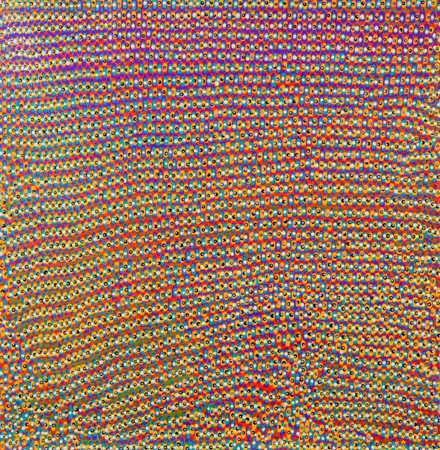

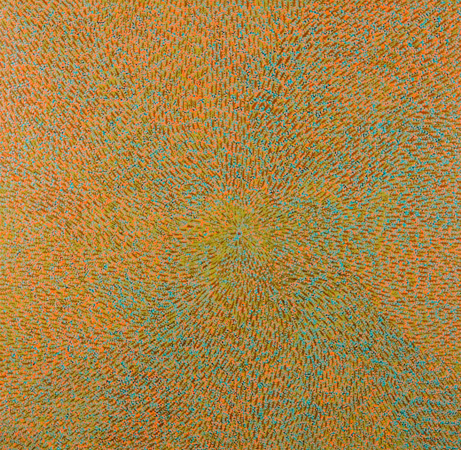

This dynamic interweave might perhaps be underpinning what Clifton mack calls his ‘moving earth’, the way he uses multiple sheets of dots and other marks in a contrasting colours which seem to shimmer with light and contain the potential to slide like tectonic plates. This process can be seen in the painting whether the subject is elemental fire embers or a landscape seemingly seen from an aerial perspective. In these constructions we see tripartite dots in a dense but logical composition: dot follows dot, colour follows colour to produce a highly contemporary resonant field, underpinned by the scaffold of landscape – a horizon line cutting across.

Several of mack’s works exist in this transitional space, where the retina is played with, colour and receding planes working against each other yet somehow in harmony. In this way mack plays with the depiction of landscape and the dynamism of the Australian outback in a way not so far removed from someone like Fred Williams. Maudie Jerrold’s paintings of fire or the bright yellow or bright orange of the emu seed bush share this same dual existence acros a very contemporary markmaking and an ancient understanding of the identify and symbolic role played by colour in the land. This process runs across a micro-level work such as Marlene harold’s image of the Mulla Mulla (“The Mulla Mulla grows in among the grass and the bushes”, she says, “and when it is is season the country looks beautiful”) or works that take on epic topics, such as when Allery Sandy paints “the beginning, when the world was soft and our Yindjibarndi law was made.” Soft worlds, moving earth, the glint fo a fire ember or the layered, hot span of the land: all of these figures exist connected in the paintings of the Yinjaa Barni group.

The painter Francis Bacon once said, “I have often tried to talk about painting, but writing or talking is only an approximation, as painting is its own language and it is not translatable into words.” Looking at works like those made at Yinjaa Barni remind us of this. Figuration, narration, the marking out of a field of vision or a territory of knowledge: these are complex texts which sit more happily in the material structure of the painting than in a foreword like this one.

We are very pleased to have the opportunity to exhibit these unique and dynamic works from this emerging group.

Dougal Phillips