The traditional lands of the Yindjibarndi encompass a vast tract of the central Pilbara region, stretching from the Roebourne costal sand plains, to expanses of desert, and through to the uplands of the Millstream, Chichester and Hamersley ranges; these areas boast some of the world’s oldest surface rocks and water sites of strong spiritual significance including Yulburr (Python Pool) and Yandanyiraa (the Fortescue river). These water sites are simultaneously sites of spirituality and survival, and along with the arid deserts and drought-resistant Spinifex grasses provide topical subject matter for local artists. The history in this region dates back 30,000 years, a story of international significance as it reflects the legends and mythology of one of the world’s great ancient cultures.

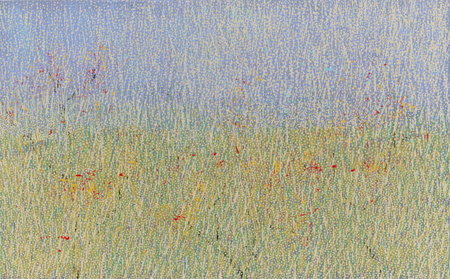

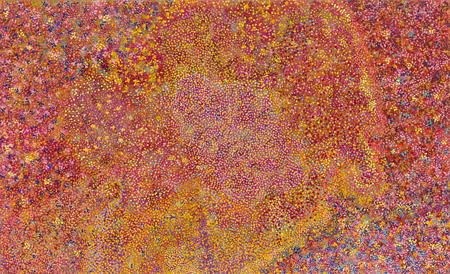

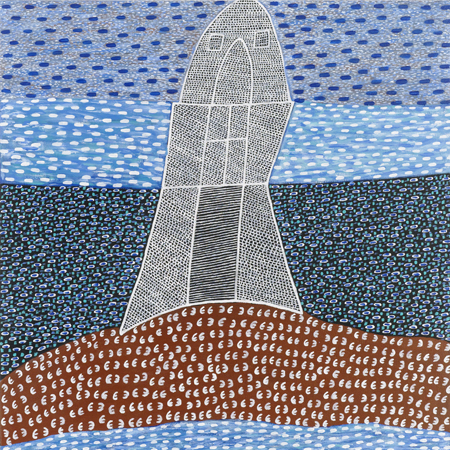

The Yinjaa Barni artists reverberate the essence of their land through their work. Allery Sandy, Maudie Jerrold and Aileen Sandy all employ triggers for mental imagery, as opposed to literal translations, as a means of presenting the spiritual history of the Yindjibarndi people. Marlene Harold and Wendy Darby both approach landscape painting through an aesthetic language that is distinctly un-European, revealing a concern with form over subjectivity via a tilted picture plane that is liberated from the confines of a horizon line and perspective point. Darby’s aerial views are vibrant galaxies that show the vast landscape seen from above where “a greater creator has sprinkled all those colours”. In contrast to these more abstract representations, Clifton Mack’s lighthouses present a very literal and figurative depiction of an iconic totem that interrupts the horizon of the local landscape.

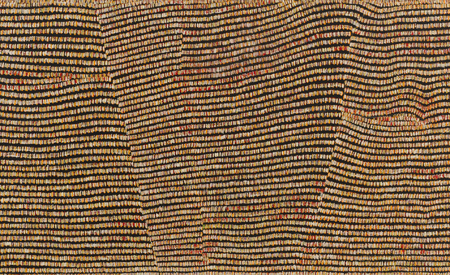

Maudie Jerrold’s Yiliway is a tribute to Minkala, the sky god who named and shaped the country and all it’s inhabitants. According to Yindjibarndi lore, Minkala created the rainbow as a sign for each year in a decade for all tribal groups. For Jerrold, the rainbow is a natural reminder of the omnipresence of this great ancestral being, a reminder that exists outside of the parameters of literal representations of the rainbow. Jerrold claims that the rainbow can be seen even in the depths of the bluest sky, or on the hottest of days looking out across the desert.

The undulating striated lines also echo another important motif in Indigenous Australian art and mythology, the Rainbow Serpent. This transforming python-like ancestral being came from its subterranean lair, creating ridges, mountains and gorges as it erupted through the earth’s surface. The rainbow serpent is known as the dichotomous protector and punisher of its people and encompasses a mythology that is closely linked to land, water, life and social relationships. The movement of the snake aligns itself with the traverse and dissection of the Australian outback by streams and sources of water.

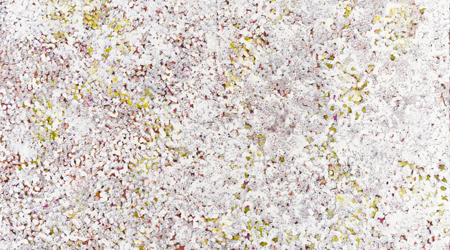

Motifs within Indigenous Australian art are often multiple and simultaneous in their meaning and interpretations, depending upon the viewer’s ritual knowledge of a site and associated Dreaming. Meanings of the elements within the artwork, whether meandering and straight lines, dots, concentric circles or spirals are imbued with significance according to the juxtapositions of designs, and the social and cultural contexts within which they operate. Combinations of design allow for a limitless depth of meaning; those that are intended for public revelation and those that are not.

In keeping with this, dotting technique is often used to mask symbolism and preserve sensitive imagery presenting a veiled field within which the action of the painting takes place. Aileen Sandy’s Jiirda, speaks of a spiritual site for the Yindjibarndi people, it is “a ceremonial place that has been passed down to us from elder to elder, it is a place where people ask for bush tucker in their country”. Sandy has used a stippling effect to conceal delicate spiritual meanings behind a web of white brush strokes. An enigmatic surface, which holds behind it hidden knowledge, tales, and magic of the desert.

The oral tradition that exists within Aboriginal culture is synonymous with a living history, one that is not stored but that is constantly evolving through inherited and contemporary experience. Yinjaa Barni in the Yindjibarndi language means ‘staying together’– for the community this finds its meaning through artistic expression which transcends history, culture, the temporal as well as the individual. While the art that emerges from the Yinjaa Barni community relates to the land it is not conceived, as is much occidental art, from perceived subject matter, rather it is a continuation of a spiritual link with the country.

In their work, Marlene Harold and Wendy Darby present a cartography of a place owned by a dreamer-painter, a place that has been marked by journeys across it – both by sacred ancestors and by the artists themselves in the role of hunter-wanderer. Darby’s experiences as a child have led her to depict the landscape from an aerial viewpoint, showing the patterns of colours and subtle markations that get lost when seen from ground level. “This is my county… As a child I would go walking through it with my mother and father looking for bush food. Everywhere, just walking through this beautiful country we call home… If we were hunting goanna through the river sand and it went over rocks and we lost its tracks, we would go up to higher ground to see where it was going.”

As an exemplary of the Pilbara style, Clifton Mack ‘s work represents the history and community of the area. Mack’s paintings of the Jarman Island Lighthouse oscillate between abstract and representation; the form of the lighthouse is a direct translation of it’s image, yet the markings that define it and shape the surrounding area are a combination of brush strokes and ancient symbols. On the ground of the island, Mack has included seagull footprints, a subtle nod to the natural elements that surround this man-made tower.

The works in this exhibition are direct in their presentation; rich in colour and texture, yet planar in nature due to the lack of horizon line. What we are presented with is an aesthetic language where the viewing orientation becomes of minor significance. The direct nature of these works convey local knowledge and ancient stories of the land as opposed to a constructed, literal narrative as we tend to experience in European painting. This work is not about how the terrain would look if you photographed it. It is about the experience of living on, and being from, that land.