Back to the Lit World

The Nine Circles by Bianca Willoughby (formally John A. Douglas) is epic theatre, distilled to video and photomedia. Its canonical tropes are all there: a maligned protagonist; a journey across time and space; encounters with advocates and tormentors; contests and challenges; an internal battle of the psyche, all intermingle with the accumulated experience of an individual living an extraordinary life in a literally extra-ordinary body.

The title of the exhibition is lifted from Inferno, the first part of Dante Aligiheriʼs epic poem The Divine Comedy (c. 1308-1320), in which the author is guided by the Roman poet, Virgil, through the nine circles of hell. The Nine Circles and its main video component, Circles of Fire (variations) has been the creative focus of artist, Bianca Willoughby since her successful kidney transplant operation in 2014. The work forms part of a trilogy of video, photomedia and performance in which Willoughby engages directly with her experience of chronic long-term illness, and treatment and interventions upon the medical patient body. The trilogy includes Body Fluid (2012), The Visceral Garden: Landscape and Specimen (2014) and Circles of Fire (2016- ongoing).

Following almost a decade of being physically grounded on Australian soil due to renal failure, Willoughby was – very quickly after her recovery from the transplant operation – deemed fit to fly. Her location shoots have since included “The Gates of Hell” in Turkmenistan, the Osoyoos Lakes in British Columbia in Canada and Hadrianʼs Villa in Rome. These places and others, across several continents, have become variously the backdrops and material for the construction of the mis-en-scene for these works, in which digital collage is used to unite significant sites, histories, characters and filmic and literary references from disparate eras and locations. The primary site for this work is however, the artistʼs own body, within and through which these accumulations of context, knowledge, history and memory are expressed.

Circles of Fire represents the journey of the artist through the sudden transitions from illness to health, and back again, and again, that are intrinsic to the transplant experience. As Lesley A. Sharp writes in Strange Harvest: Organ Transplants, Denatured Bodies, and the Transformed Self (2006),

“In essence, a transplant marks the beginning of yet another sort of chronic condition that can extend to the end of oneʼs life…They risk an onslaught of infections, where even a common cold might evolve into pneumonia and land them in the hospital.”

But it is still a life, though risky and uncertain. In the dual screen video, her characterʼs body, shrouded in white, is marked like an anatomical model by a renal diagram that courses across her abdomen. As in Inferno, the artist protagonist leaves the world of light, and travels through a series of startling settings and encounters, including a descent into eternal fire, flight over the healing waters of a sacred “spotted” lake and a stylised surgery in which his shroud is cut and jewels are arranged with precision on his exposed skin. The trauma of this surgical event is presented in the video diptych by the artistʼs thrashing, isolated form on the left-hand screen, while a female ʻsurgeonʼ on the right- hand side attempts to contain blubbery viscera on a flat table, creating a disturbing interplay of horror and comedy that are characteristic of Willoughbyʼs work.

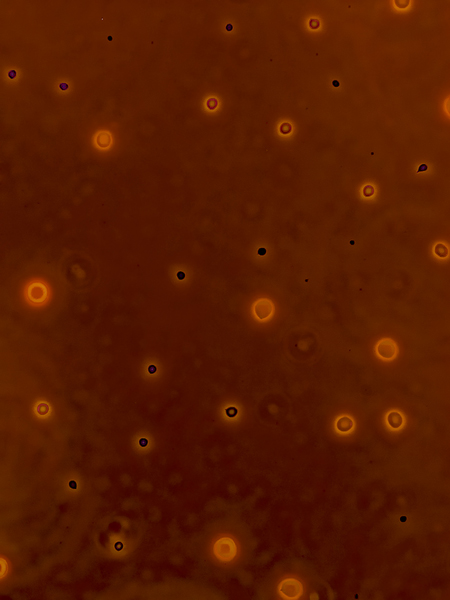

The artistʼs jewelled body later passes serenely over a field of illuminated pinpoints and circles of light that prove to be digital microscopy images of her own T-cells, rendered as a multi-coloured constellation. In her lived experience as a transplant recipient, these leucocytes are suppressed in order for his body to accept the transplanted organ. Three still photographs in the exhibition also represent these blood cells, which are like self-portraits of the artist at her most basic level. They represent his immune system, which has kept him alive for most of his life and which post-transplant, continually threatens the new arrangement of his body with its functioning kidney.

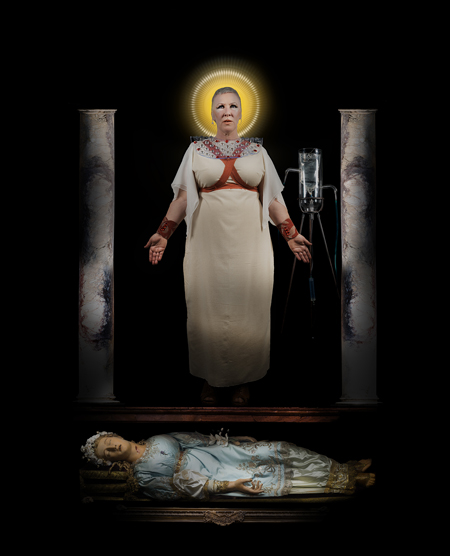

Throughout her trilogy of works, Willoughby has researched and documented natural environments that are analogous to particular internal states – saltpans, ossified coastal cliffs, deserts, lush forests, swamps and rivers – and in this photographic accompaniment to Circles of Fire (variations), man-made ruins and historical sites including classical-period hospitals, and early operating theatres. Three images, The Vascular Surgeon, Infermiera and The General Surgeon use framing devices familiar to religious altarpiece painting of the Renaissance, a triptych with haloed figures enclosed by columns and pillars. The Vascular Surgeon depicts a woman (artist, Celeste Aldahn) in stylised costume bearing surgical implements, looming over the supine wax figure of an Anatomical Venus from the Museo di Palazzo Poggi, Universitaʼ di Bologna. The General Surgeon depicts a man (artist, Yiorgos Zafiriou) similarly attired and standing behind a marble dissecting table from the Anatomical Theatre of the Archiginnasio in Bologna. Infermiera, the central image of this triptych, features the surgically costumed figure of artist, Stella Topaz, a burlesque performer in real life whose profession is in LGBTQI health. At her feet are the “incorruptible” remains of Saint Victoria, her embalmed body preserved in wax. This grouping of works draws-out the support characters appearing in the video Circles of Fire (variations), and their representation of the individual doctors and nurses who saved the artistʼs life – preserved now as idols, like the saints and idealised bodies they are arranged in composition with.

Willoughby’s body is of course, a coexistence of bodies, of both her and her donorʼs, and her survival is in part dependent on the community of health workers suggested in these works. In a final photographic collage, shot against a backdrop infused with sunshine, Willoughby superimposes her hands proffering a shiny, glass kidney, Intruder (2016) against a background of sand dunes that support and encroach upon classical ruins of statues and columns – reminiscent of the poem, Ozymandias (1818) by Percy Bysshe Shelley,

ʻMy name is Ozymandias, king of kings: Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!ʼ Nothing beside remains. Round the decay Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

Shot from the point of the artist, her hands present the kidney as an offering-out to a desolate, destroyed environment – a sacrifice, a gesture of continuing life against the forces of death and decay. As with Danteʼs descent in Inferno, our hero returns to the lit world.

Bec Dean, 2017

This project has been assisted by the Australian Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body. This project is supported by the NSW Government through Create NSW.

Principal Artist: Bianca Willoughby Associate Producer: Bec Dean Performers: Bianca Willoughby with Celeste Aldahn, Stella Topaz, Yiorgos Zafariou Performance Director: Sue Healey Videography: Bianca Willoughby, Dara Gill Ariel Videography: Rubicon Cinema (BC, Canada) Lighting: Bianca Willoughby, Martin Fox, Mark Mitchell, Yiorgos Zafiriou Editing, Compositing and Colour Grading: Bianca Willoughby Digital Stills collage: Bianca Willoughby Soundtrack: Justin Ashworth and Glam Cyborg (Celeste Aldahn, Freya Adele) Arrangements, Sound Design and Mixing: Justin Ashworth and Bianca Willoughby Costume Design and Production: Michele Elliot, Yiorgos Zafiriou, Bianca Willoughby, LED Costume design production and rigging: Alejandro Rolandi Props Design and Production: Bianca Willoughby Nadege Desgenetez (glass objects) and Yiorgos Zafiriou On Location Production Management and camera operator: Melanie J Ryan

Special Thanks to: First Nation Okanagan custodian of Spotted Lake(Kliluk), Alex Louis (Senklip Skalwx) for permission to perform and shoot at Spotted Lake, BC, Canada. Artik Gubaev and Batyr Nitazov for clearance and transport in Turkmenistan. Dr Stuart Hodgetts, Assoc Prof Silvana Gaudieri, Guy Ben-Ary and Celeste Wale for assistance with the artist’s T-cell experiments and microscopy and Symbiotica Lab, UWA. Museo Palazzo Poggi, Bologna, Italy for permission to photograph in situ Clemente Susini’s anatomical wax venus, Venerina, 1782 Ingrid Bachmann, Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada Andrew Carnie, Winchester School of Art, Southhampton University, UK Helen Pynor, University of London, United Kingdom Kate Scardifield, University of Technology Sydney, Australia

The artist gratefully acknowledges the support of The School of Art, ANU Canberrra, ACT, School of Media Arts, UNSW, Symbiotica Lab, UWA. and The Bundanon Trust.

The artist would also like to acknowledge the first nations people of the Osoyoos Indian Band (BC, Canada), the Yuat of the Nyoongar Nation (WA), the Gadigal of the Eora Nation (NSW) and the Turkmen of the Karakum Desert (Ahal, Turkmenistan) on whose land this work was made.