“Certain thoughts are prayers. There are moments when, whatever be the attitude of the body, the soul is on its knees.”

– Victor Hugo, Les Miserables: Chapter IV, 1862

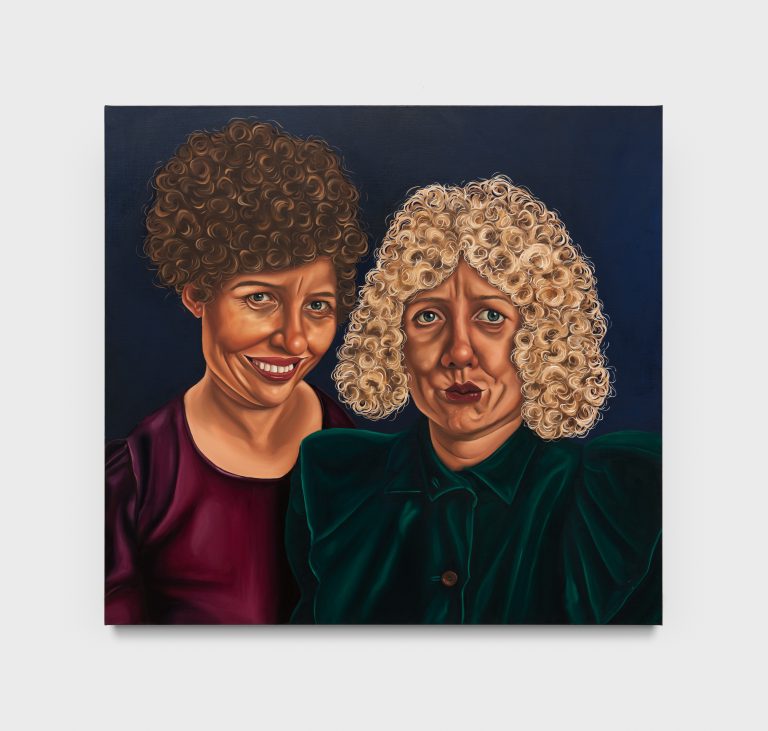

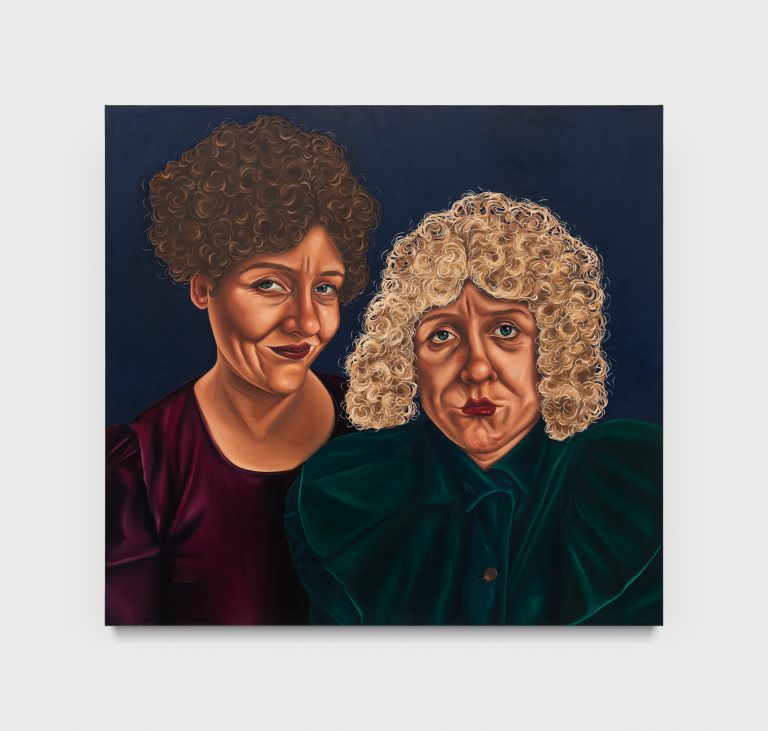

Sophia Hewson’s adoption of her subjects enables re-enactments of past histories and mythologies, which in turn offer an updated iconography. Highly finished paintings and sculptures succeed in conjuring the religious and mythological, but on the other hand speak directly to an unmistakable Pop aesthetic. A dichotomy is being played out: the seriousness of the content is carried through the titles, yet they are also being confused by a kitsch presentation. I can feel myself forming (my borrowed rib), But like a slug I am mighty to men gives us a naked and crying Virgin Mary wearing a synthetic polymer veil, a fluffy halo and a plastic flashing heart around her neck, uncannily realistic in its rendering this character could well play a part in one of LaChapelle’s tableaux.

Aligning itself nicely with the Hyperreal of the 1980’s & 90’s, Hewson’s painting presents the subject in a way that distances the object from the artist. Authorship is confounded, the ‘hand of the artist’ is not represented by a gestural brushstroke, and a thick layer of resin serves to further create a barrier between the signifier and the signified. Bound in a thick, syrupy resin, like prehistoric insects in amber, Hewson’s subjects are

perpetually suspended, preserved and distanced. But almost paradoxically through this shiny surface, and

iconicity, the Sublime and spiritual seem to be suggested.

Both the content and process embodied in these works pushes towards a cathartic redemption from an

inexplicable, omnipresent, malady. Hewson attempts to find a means of genuine salvation and spiritual elation, and through doing so simultaneously captures the sadness or mourning that is embedded within the inevitable inability to find such fulfillment. This ‘longing’ is present in the show’s title which pays homage to a small planet thought to have been discovered by a French mathematician in the 19th Century. The planet, named Vulcan, was soon disproved to exist. This hypothetical world whose life was so short speaks of an ontological yearning for something that has not truly been lost but has left a void regardless.

It could be argued that in our secular and multicultural society shared values as outlined by the codex have

dissipated and been replaced by the popular, the common, the everyday. Is Sophia Hewson’s art calling for a

contemporary reading of religion and universal, traditional values? Or is it all surface, where Madonna is more likely to conjure the pop icon rather than the religious? Neanderthal Christ, suspended in a structureless

crucifixion, carries the gravitas of Renaissance art history yet also taps into a shared knowledge: that of hundreds & thousands on fairy bread, or cupcakes, an ingredient that can be sourced from any supermarket.

Similar is her approach to Help me Saint Teresa of Avila, with the saint presented as a Renaissance-like tondo sculpture, carved by hand and then cast. St. Teresa, a Carmelite nun and Spanish mystic, is famed for the religious ecstasy she experienced during a bout of feverish illness. Outlined in her own writings, St. Teresa claimed four stages in the path to achieve union with God. These steps to ascent followed moments of increased intensity in mental prayer, culminating in “the devotion of ecstasy”, a climactic state involving the loss of consciousness to divine intoxication. Teresa claimed to have been visited by a seraph armed with a gold spear headed by a small fire, which he used to pierce her body numerous times, drawing out her entrails and leaving her in a state where “the pain was so great, that it made me moan; and yet so surpassing was the sweetness of this excessive pain, that I could not wish to be rid of it. The soul is now satisfied with nothing less”. [1]

It would seem that in the experience of the ‘unmanifested’, through sexual/spiritual ecstasy from tactile/cognitive sources, there is a reoccurring conjuncture with something darker that lurks beneath the surface. Perhaps it is the uncertainty of the experience, or the subconscious implications: the proximity between “la petite mort” and actual death, between pornographic orgasm and divine rapture. As Bataille says, “the bond between life and death has many aspects. It can be felt equally in sexual and mystical experience”. [2]

There is a tension in Hewson’s work between high seriousness and Pop, between pastiche and true experience. The work takes everything equally seriously, from the fashion photo to hagiography; as our contemporary experience takes in such a disorienting breadth. Hewson’s paintings and sculptures act as aides to help us understand and confirm the challenges of our late capitalist existence where we are often just set adrift, with little to hold onto.

– Kat Sapera & Oliver Watts, 2011

[1. St Teresa of Avila: El Castillo Interior, 1577 | 2. Georges Bataille: Death & Sensuality, 1986]