Certain rituals and images mediate our sense of self and our position in society. In public, and in private, we perform a role or job that is to some extent always detached from the ‘real me’. As a nation, we also go through this process of self-definition – through Henry Lawson poems, through bush and beach culture, and through historical narratives and cultural artifacts such as film and television. Is there in fact an Australia past the fictions?

Bianca Willoughby’s work uncovers these images of ideology (with a particular focus on film) and ‘Strange Land Vol.1’ continues this ongoing exploration. The setting of the various scenes is Glen Davis, and it becomes a metaphor for a Golden Age of rural/industrial Australia now passed and passing: a shale oil mining town whose heyday was in the WWII period. Since its closure in 1952 it has become a ghost town. The cast of characters in this work comes from this nostalgic time when perhaps Australia felt it knew itself more clearly – even the landscape becomes signified as the archetypal McCubbin / ‘Mad Max’ backdrop of Australian hostility and beauty.

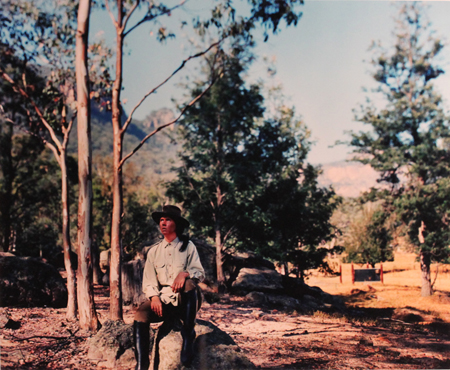

There is the squatter pioneer who walks the line, surveying. The young seminarian conflates the difficulties of enculturating the hostile landscape with the difficulties of masculinity; the rituals of drinking resonate with church rituals and it is a weird coincidence that the seminary in town (after the priests left) was turned into a pub. There is the good English wife desperately trying to civilise her surroundings; the waitress/horror actress; the good miner/worker; the WWII scientist/contamination expert. In a comic twist, as if clutching at straws, it is the gold alien that offers the last chance to understand the strange filmic qualities of the place.

Willoughby’s work proves how these images still persist as ideological and psychological markers. The miner for example is a very powerful image of Australian health and manliness, from the heroes of Beaconsfield, to a mining tax that toppled Kevin Rudd. This video installation on one hand celebrates these images but on the other declasses them in critique; it is hard to tell whether the work is a nostalgic utopian dream or a horrific and cynical debasement.

Willoughby’s co-conspirators are the Western Sydney performance artists Sari T. M. Kivinen and Liam Benson. In an attempt to probe the psycho-geography of the site both performers draw on their own practice and experience. The performances remind us how everything is in part fictitious and constructed. The character of Starella, has been used in many guises by Kivinen before and here lands in town disorientated and scared; the complexity of this self-referential layering again highlights the way in which the images accrue all slightly morphed and unclear: the horror scene is borrowed from ‘Chain Reaction’ (1978), that was shot at (and has subsequently become part of the history of) Glen Davis.

Similarly Benson’s priest elides the town’s ghost story of a novice’s suicide and the film ‘Devil’s Playground’ (1976) (that also played with the tension between desire and religious discipline at a seminary). Benson brings her own experience to bear on these issues of faith and liberty. Another important filmic reference is the haunting soundtrack by the composer Debra Petrovich, whose credits include among others, Tracey Moffatt’s ‘Night Cries: A Rural Tragedy’ (1990). Sound also becomes and important signifier of place and the politics of identity.

From art history to film, from performance to cinematography, our understanding of Australian culture is made up of images and dreams that resonate and contradict with one another. Through a thorough study of Glen David, Willoughby shows how fragile this set of allusions is on which we base so much of ourselves and our place in the world.

– Oliver Watts