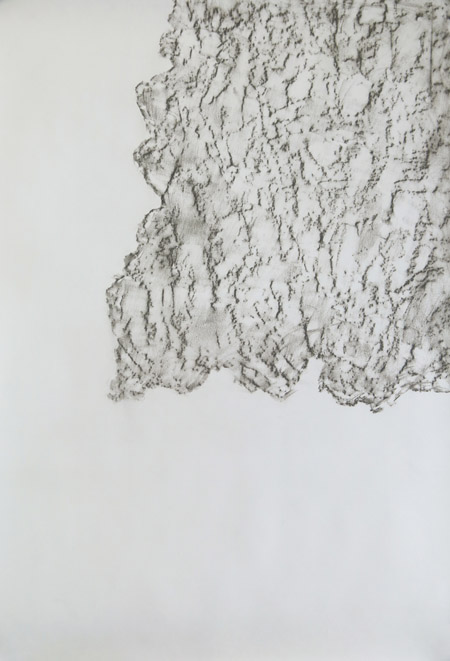

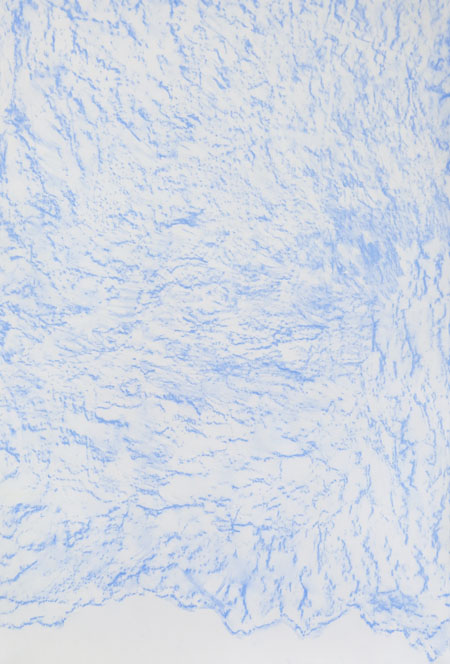

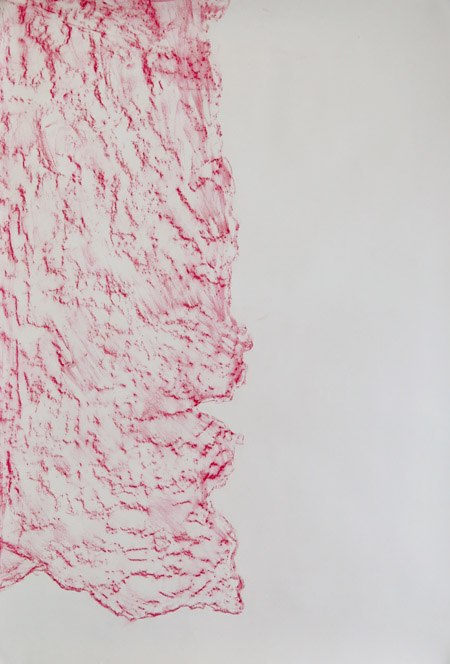

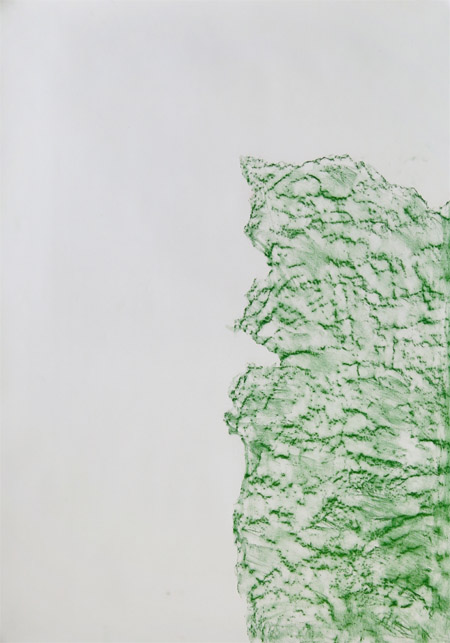

In 2013 Mathew McWilliams was invited, along with three other artists, to take residence in Rivodutri, a small town in Italy – to develop a site-specific project that would be exhibited over the course of a year. Each artist was allocated a season. In spring, McWilliams chose to engage the town’s alchemic arch and a series of frescoes, relocated – in fragmentary form – from a little chapel that was damaged in the earthquake of 1948 to the town’s parish. The project was realised in two series of works on paper: Relief, which uses coloured conté crayon to make surface rubbings on paper, and Relief (uncoloured), which results simply from pressing the paper into the edges of the cracked and irregular borders of the fresco reliefs following it’s contour only to reveal dirt and shadow. Originally installed on location in Rivodutri, at Chalk Horse the gesture again becomes one of relocation.

McWilliams’ use of frottage (rubbing) employs a temporary mask in order to elicit the substance of the frescoes. On one hand, the results were renderings of the positive spaces of the frescoes that took colour references from the original works to create monochromatic, abstract drawings. On the other hand, the frescoes were negated through the use of veils. By concealing the images on the chapel walls, artworks normally taken for granted by regular parish visitors were revived in the eyes of their audience.

Minimal in their execution, McWilliams’ works translate the original paintings into maps that both reference the subject and formal content of the originals. He notes that “frescos are a kind story telling (allegory) but are mostly found and experienced in fragments, which becomes a kind of abstraction. I’m bringing this to the surface psychologically and physically.”

Frottage in art is an automatic drawing technique developed by Max Ernst in the 1920s and used by Ernst and his contemporaries within collages and paintings. McWilliams’ use of frottage began a little over three years ago, with a project that saw him taking impressions of the ground directly in front of artistic ‘masterpieces’: from ancient artefacts to Francis Bacon paintings, Agnes Martin paintings, and other offerings labelled as ‘art’. In Rivodutri, McWilliams identified the frescoes as source material for a new series of frottage works, employing the technique as both documentary and creative tool. Astonishingly, after proposing the project, he was granted unlimited access.

“The church became my studio – I had absolute freedom, which could really only happen in a small town. In fact the curator of the project, Luca Arnaudo, strategically focuses on small, neglected towns. He believes that villages hold possibilities that larger cities are not able to explore… and some of the towns still contain wonderful secrets”.

On searching for ‘Rivodutri frescoes’ in Google, the second result to appear – after ‘Earthcams’, a website linking to web cams around the world – is a review of McWilliams’ exhibition from 2013, in an Italian magazine called ‘Dude’. Which exemplifies the way that artists and curators working today are increasingly changing the way histories are written and knowledge is produced. McWilliams’ project not only ‘maps’ the fragmented frescoes, and their physical relocation, but also maps the town and its histories.

So just how did a mostly-Paris-sometimes-Sydney-based, Canadian artist end up in Rivodutri, a tiny village in the literal, geographic centre of Italy, to ‘map’ the frescoes assumed to date back to the XIV century and attributable to the Umbrian school? The answer is perhaps most apparent in the work – that conforms to the artist’s ongoing process of historical and cultural excavation, manifest as conceptually rigorous, poetic gesture. As an Australian, I cannot help but connect McWilliams’ images with aerial maps, or to our relationship with expanded notions of landscape, and the way desert paintings are made. Which is the lovely feature of McWilliams’ abstracted forms and his singular approach, that applies his personal experiences to trans-cultural and trans-historical subjects, both within and beyond the confines of art.

Tania Doropoulos, 2014

1.From email correspondence with the artist, March 2014.

2.Ibid.