Artworks

Installations

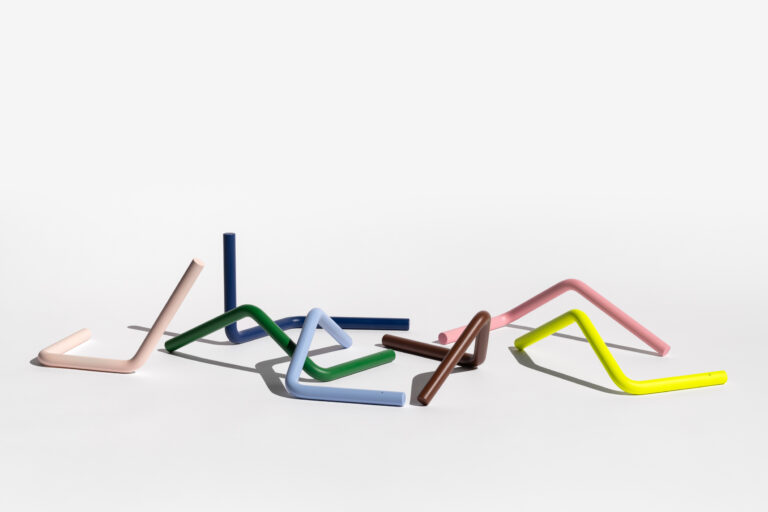

PIN

“How are we to speak of these common things, how to track them down, how to flush them out, wrest them from the dross in which they are mired, how to give them meaning, a tongue, to let them, finally, speak of what it is, who we are.”

Georges Perec, Species of Spaces (1974)

Look up ‘pin’ in the dictionary and you’ll find a word with so many meanings it has a collection of sub-categories to help you refine your search. Do you mean ‘pin’ in relation to jewellery, medicine, weapons, music, electronics, golf, games, or finance? ‘Pin’, as in a piece of metal with a round head that is used to fasten cloth; a steel rod that is used to heal fractured bones; an ornament; a peg that secures the lever of a hand grenade; a skittle or a pair of legs or a bank passcode; the flag pole used to mark a hole’s position on the golf course; or a hair or a bobby or a safety pin? (This is to say nothing of pin-adjacent words, such as the humble cushion.)

The pin, in all its uses and forms, remains ubiquitous and ordinary. It exists as a mere functionary, a go-between immersed in the world of the uneventful. It’s a mundane implement that wishes, always, to be of service: to support, to tether, to cap, to puncture, or to take the strain. How, then, to describe the titular pins of Rocket Mattler’s exhibition, pins that contain many of these descriptors but also none of them at all? The easy answer is to say that they are reinterpretations of scaffolding pins, a kind of pin that is used to “attach accessories to scaffolding, such as guardrail posts, screw jacks and more.” (They come in a variety of shapes, sizes, and weights, from the toggle to the hitch, to, my personal favourite, the ‘pigtail’.)

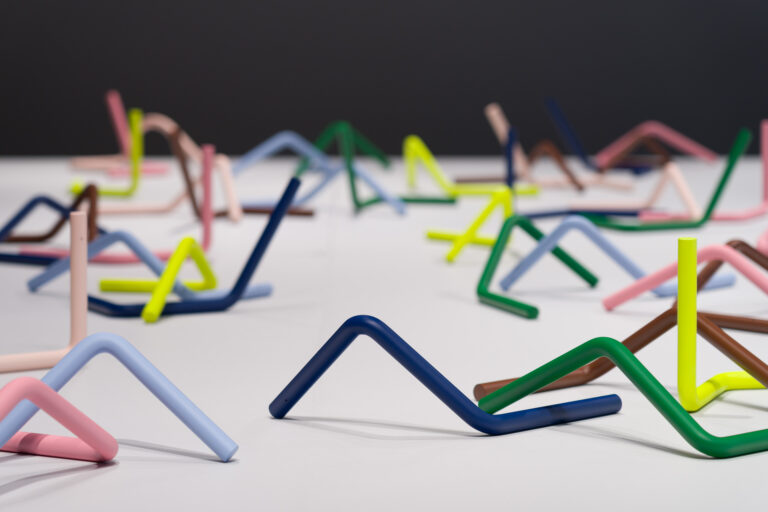

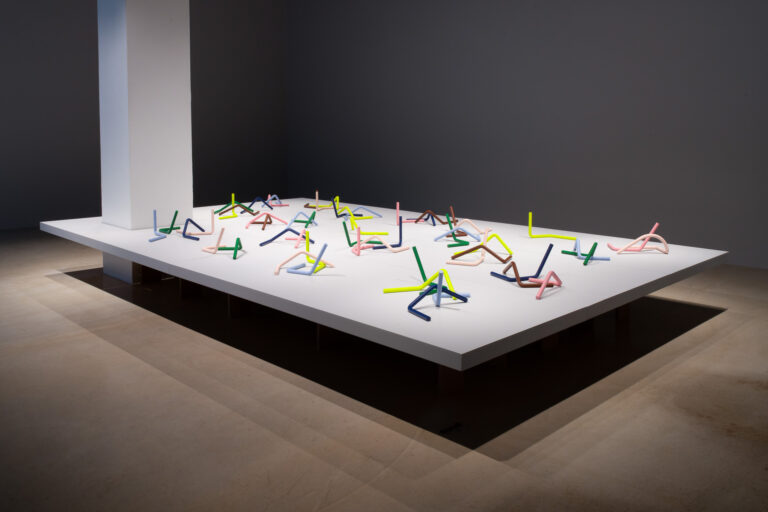

Here, Mattler has taken a specific scaffolding pin, one sold at a hardware store in Santa Monica, as his starting point. By refashioning this particular pin—by drawing attention to its edge, shape, and line—Mattler has transformed this object into a series of sculptural forms. Released from purposefulness and the need to support something else, these pins have found themselves as the main event. Mattler is asking us not to look at what is being pinned, but at the quotidian contraptions we barely take the time to apprehend. There’s another shift happening too: as replicas with no industrial purpose, these pins have had their use-value removed. They can no longer participate in the hierarchy of the productive and the functional, and so are given the chance to rest, perhaps even to luxuriate, in their own design.

This isn’t to say that Mattler is deifying or revering the pins. He’s not precious about them, and we can rearrange these sculptures into an infinite number of combinations and points of relation. We can tilt them on their side, combine one colour with another, balance one on top of the other, or change the colour order once again (all the blues together this time, with the rose pink next to the chocolate brown). We can play.

But wait, isn’t the pin (as both a noun and a verb) preoccupied with stasis, with fixing, fastening, sticking, nailing, attaching, and restraining? Not these pins, with their shape-shifting and open-ended tendencies: they make room for tinkering, pottering, dabbling, messing, puddling, and trifling. In this way, these forms—should we even call them pins?—embody what Maurice Blanchot claims is the one essential trait of the everyday: they allow “no hold”. They escape.

Naomi Riddle, 2023