Curated by Andre de Borde & Jasper Knight

“I had become addicted to shooting, like one becomes addicted to a drug.” Niki de Saint Phalle, [on why she ceased making shooting works, 1963]

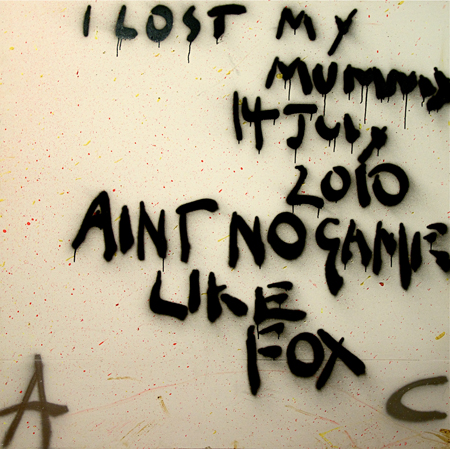

The paintings in this new series are characterised by yearning. Although many of them have been shot at in various ways the work is paradoxically not bombastic. Soft pinks, dry brush techniques and a high colour palette formally create a set of sunny, fun and bright works. Obviously there is loss here though too. Ain’t No Game Like Fox, is a text work, that proclaims, like a eulogy, Cullen’s pain after recently losing his mother. It is loss and calling out for help or support that is at the heart of all this work. They are works of great honesty and intimacy.

In this series, Cullen uses shotguns and .22 Calibre (small) rifles, to iconoclastically rip at the canvas. Paint is applied not only through a textual, graffiti approach, but also by shooting at pots of paints and spray cans. In one sequence of the video footage showing the creation of the work, an aerosol can is shown spinning balletically in front of the canvas as it leaves curves of colour behind it. So there is a chance element to the work that suggests a renunciation of the surety of the authorial position. The mode of working is not novel and recalls the Shooting Pictures of the neo-realist Niki de Saint Phalle (c.1961-1963). In this context it was a satirical joke against the grand heroism of the abstract expressionists (Pollock, De Kooning et al.) who the neo-realists vehemently disavowed.

By extension, in these works, Cullen is self-critical against the heroism of his gestural marks that we see commonly in his large figurative works. In fact even stylistically – the use of spray paint, the text, the thinner searching line, the large areas of plain white canvas – they recall the early grunge work (1993 and onwards Yuill/Crowley; Life Fitness, Artspace, 1997). At this time the authorial, star artist was questioned in his work through appropriation, use of found objects and through open juxtaposition of images where iconography failed to coalesce. An anxiety has returned. The grunge use of found objects can be seen here too as the guns are part of Cullen’s studio, something he collects (his brother is a master knife maker) and the paint pots and aerosol cans are similar detritus.

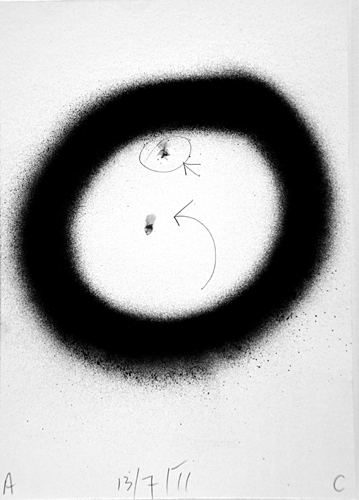

It is important to understand how these works are not about an attack but a plaintive call. All ballistic work in art is not really ballistic because it is already mediated by art (see for example: the gunpowder work of Ai Weiwei and Cai Guo- Qiang; the shotgun and paint can works of William S Burroughs; Yoko Ono’s Das Gift 2O1O; and even Chris Burden’s ‘Shoot’ 1971). Shooting at a canvas is by its very nature impotent; there is no external target or result merely a feedback loop, a ricochet. The work is not violently and passionately made but safely: they are done on private property; with legal weapons; in a creative not destructive act. It reminds me of the number of “assassins” that have shot at the Queen, Presidents, Popes and other celebrities. From a psychoanalytic, criminological point of view the pathology of these people is a hysterical one. They are calling out like a child for someone to soothe them. They do not want to destroy the target, on the contrary, they want to be recognised by them. They do not want a revolution but instead actually want the target to be a “better”, more just, more responsive figure.

By violently acting out, Cullen is calling out for people to react to complete the work: will the police come; will friends come to respond to Cullen’s loss. This hysterical mode also can be seen in Cullen’s Ned Kelly series. This is not the rebellious Kelly of the myth that violently overthrows the oppressor (see Mick Jagger’s Irish rebel). This is not Nolan’s Kelly as outsider, a subaltern that does not find justice. Cullen’s Kelly is a joker/fool, with Viking horns added to the helmet. It is a play-acting Kelly who questions the authorities about the quality of their justice and equality like the artist/fool critiques the king.

The paintings ask the viewer, “Look at me, look at me.” In .22 Cal’ X and Rick O Sha’ for example Cullen even supplements the bullet holes with arrows and signs as if you may have missed them the first time. This is the classic, hysterical doubling. The series is a process of acting out, and within the canvas this process continues. The holes and ripping of the canvas also seem to suggest or question the ability of the message to get through. For Cullen in this series painting itself seems to fail and is unable to carry enough of a message, but he will continue to try.

In the end though the work speaks to all of us. We have all at one time or other cried out to be recognised and cared for. We want our wounds to be dressed by our nearest and dearest. The work is hopeful that someone will listen. Indeed if the “squeaky wheel gets the oil,” it is the hysterical crying that often does in the end lead to a better a justice or a better understanding in society. These little insurrections then, contained within a canvas, do perhaps suggest the seeds of change and love.

– Oliver Watts, 2011