Artworks

Installations

“You will see doors open on fields of snow under blue skies, fireplaces furnished

with clocks and swinging wide to serve as doors, and palm trees growing at the foot

of a bed so that little elephants standing on bookshelves can browse on them.

As to the orchestra, there is none…The action, which is about to begin, takes

place in Poland, that is to say: Nowhere.”

Alfred Jarry, in a speech before the debut performance of Ubu Roi at the Theatre Nouveau, in Paris, 1896. The palm trees may have been painted by Toulouse-Lautrec.

By the early 2000s, the Palm Grove of the Royal Botanic Garden Sydney had become a “skanky mess” according to its senior horticulturist Paul Nicholson. The palmetum had been the pride of the Garden’s directors, the botanical collection the institution was most famous for, and it took a long time, more than a century, for its fruit-laden trees to attract bats in serious numbers. But when they came, 27,000 of them at best count, they chewed and shat and mated until the Grove was a muddle of reseedings and zoonotic disease. Once the colonies were relocated (using sound) it took years to reconstitute the plantings, and needed the help of private palm collectors, middle-aged men who mai ntain huge, secretive plantation estates on Australia’s east coast, and always wear shorts.

The fate of the Grove expresses a quirk of the wider city. Palm trees are everywhere in Sydney, but they are not emblematic of the city, in the way they might be in Miami, Honolulu or Los Angeles. Beyond the competition from iconic species (Moreton Bay figs, jacarandas and gum trees for example) they occupy an uncertain status that has never been fully resolved. They are both a decorative presence, and something that threatens to become wild and unruly. It is an ambiguity that can be traced to the early colony. There are two species of palm native to the Sydney Cove area. They were probably never common, confined to glades and valleys, and within a few years of invasion they had been felled so completely that none are visible in early post-settlement depictions of Sydney Harbour.

Ignorance helped. The Gweagal had cut steps into the palms’ trunks to climb up and harvest fronds; Europeans cut them down instead. Prized as a building material, the “cabbage tree palm” was also one of the few Aboriginal food sources Europeans knew how to prepare and consume. The plant also yielded perhaps the first home-grown item of colonial Australian clothing, hats were woven from their fibres by convicts. They became distinctive of youth gangs called ‘cabbage tree mobs’, prototypes of the larrikin and the eshays. Once the harbour was denuded of these trees, they had to be sourced from the coast, north and south, where they inspired place names like Burning Palms and Palm Beach, just as they had given the Dharawal people their name.

It was the beginning of a strange sequence: first settlers removed the native palms, and then, almost a century later, began replanting replacements. Some were sourced domestically, many more internationally, and the appreciation of them had to be imported as well. The Garden’s longest-serving director, Charles Moore, became entranced by the palms after a speciman-collecting voyage in the South Pacific. On his return, he and his successors drew from huge international trading networks in plants and seeds that were tied to imperial possessions. First they filled the Palm Grove, greenhouses and garden beds to bursting, and then propagated the surplus all over the city.

Exmplars were shipped from Senegal, Tonga, Cuba, Reunion Island, China, Chile, and their green offered rare visual relief in what was then a dusty, rough town. Tall Phoenix palms lined Macquarie Street, and they were chosen as avenue plantings in Centennial and Hyde Park as well. Often placed alongside neoclassical architecture where they could act as living colonnades, they still flank many major sandstone buildings in the city: The Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney Hospital, the Mitchell Library, St Mary’s Cathedral, Kirribilli House – each has them in attendance, and city planners in the new millenium still favour palms. Cheap and resilient, they readily survive replanting, and provide an instant illusion of longevity in places like Chifley Square.

Beacuse they are so often used as a framing mechanism for structure, Sydney’s palms are often upstaged, and even for species not pushed into cameo roles botanists sometimes talk about “plant blindness”. This is the tendency, after modernity, for flora to recede from our vision. In natural environments we might suffer a “green wallpaper” effect, where plantlife en masse becomes indeterminate. In the built world, individual plants can become as anonymous as faces in a crowd, and palms have a unique means of disappearing. Too big to miss, they can neverthless be difficult to perceive from close up. City walkers can often experience them as forgettable, indistinct presences, “a telegraph pole with a green tuft on top” as one botanist put it.

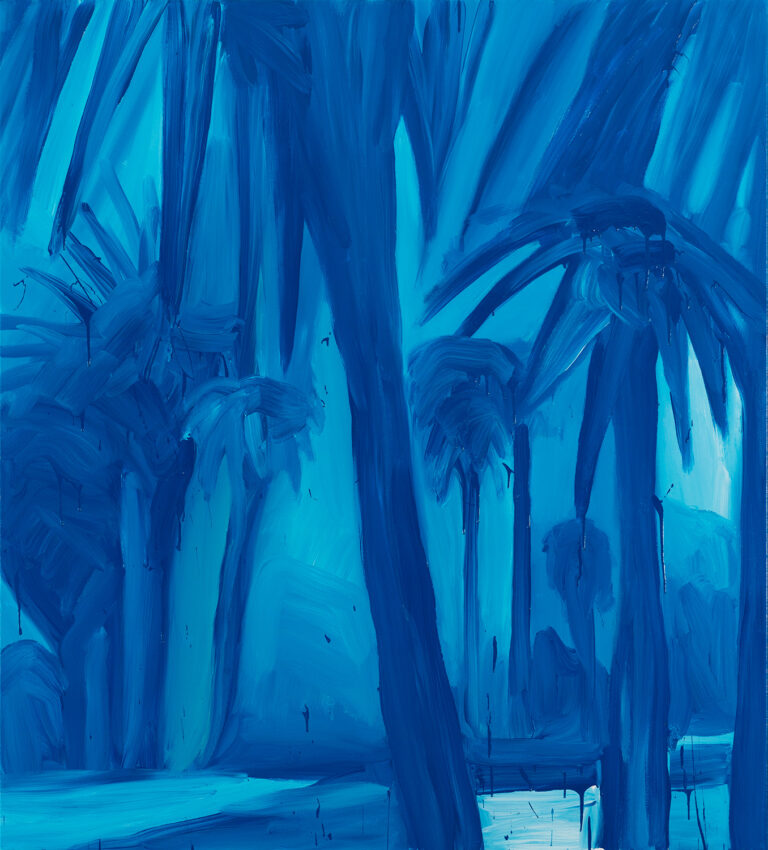

In FIREWORKS, Jasper Knight gives these ever-present trees his full attention. Many of the 112 palms depicted can be found in Sydney (painted from internet photos, not life, as is his practice). A few come from other places, or his imagination. There is freedom in this unity of subject, expressed through a radically curtailed palette, and it’s a freeing that comes from release. Instead of Jasper’s signature primaries in concert, we are in a blue period: most of these paintings draw only on four shades of blue, along with a white. It’s been said of Jasper’s construction works that the surface does as much work as the paint. Here, when board, metal and perspex are replaced only with linen, the paint has to work harder. That’s unforgiving, and so is his brush selection, broad-gauge house-painting brushes from Bunnings Warehouse, that need extra surety and confidence to wield. Jasper has always painted best when painting quickly, and that dynamism motivates works like Centennial Palms, in which a palm’s crown can be rendered in a dozen thick strokes. It’s a spontaneity that extends to the subject as well. There is no craggy mountain range on the horizon of Centennial Park, and nor, in real life, do the avenue palms occupy such an ordered perspective on level, horizontal ground. It’s subtle, but the artist is altering the whole landscape to compel noticing, layering what the eye can compile only through distinct glances.

Jasper is also in conversation with an art history of Western fantasy landscapes. There are, for example, whole lurid jungles of palms in Henri Rousseau, who saw them in greenhouses in the Jardin des Plantes, where he could “enter into a dream”. Their role as signifiers for the exotic or unknown further confounds their disappearance and reappearance in Sydney. In spite of their planters’ desire to evoke some indistinct, exotic other place, they also recall this place, before contact. One variation of this tension peaked in the 1970s, when a craze for queen palm trees tried to conjure the leisure and glamour of tropical resorts in the middle of suburbia. Residents with visions of piña coladas instead found themselves under a hail of bat shit, and arborists blunted their chainsaws working through the fibrous trunks. The species is now considered a weed in New South Wales.

FIREWORKS is full of such double-edged promises, things that aren’t as they seem. Even classifying the paintings as “landscapes” is a mistake; look carefully, and they are closer to still life, or even portraiture. Take The Departed, in which ultramarine splayed fronds border a sharp, modernist skyscraper. What could be a vignette of a twentieth-century American city is in fact a park pathway that looks onto the T&G Tower on Elizabeth Street. The trees are probably Senegalese date palms (even experts can struggle to identify them) replacements for originals felled by a fungal disease. The effect is uncannily cosmopolitan: though the work is named after the Martin Scorscese movie set in Boston, Jasper thinks it looks more like Miami. Today that city is rife with foxtail palms sourced from the Northern Territory, which haved turned sickly in the alkaline Floridian soil.

The Departed is not the first of Jasper’s works to feature the palms of Hyde Park. His 2012 project Friendly Billboards (a husband-and-wife collaboration with the architect Isabelle Toland) placed LED signage around CBD streets, offering a luminescent commentary on the state of the city. The sign that sat next to a dense crop of sugar palms in Hyde Park broadcast the message HIDDEN TREASURE? Those palms have since been removed, but another of these unauthorised groves remains, subverting the best-laid Beaux Arts plans of the park. That grove has grown into a thicket deep enough to hide things, and between the trunks are remnants of homeless encampments, and a bower of coloured balloons and silver nitrous oxide canisters, signs that the jungle comes alive at night.

The keystone work in FIREWORKS might be Luna Palm. It’s a view of one of those Phoenix palms that grows in the shadow of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, just near Milson Point ferry wharf. It’s abstracted into an almost Munchian exploration of form and colour, its layering of volume and light (buried under there is an abandoned study of a boat). Jasper has produced more than 5,000 works now, and most owe something to this same harbourside terrain, the places in which we grew up. Jasper’s father John believes, half-seriously, that all of his son’s works draw inspiration from these early homes and neighbourhoods (—“Cars in Paris? His mum used to drive a Renault”—) and that the apparent exceptions are just missing links.

John is right that some of the indirect traces can still be identified. I’ve wondered if Jasper’s car paintings might owe something to an eccentric North Sydney dealership called the Toy Shop, where we used to admire an unsaleable Porsche 924 (“the people’s Porsche”) with a signal green livery. Others, as with his frequent paintings of northern harbour wharves and tugboats, are more literal. Luna Palm puts this show into the second category. There are palms in front of the Kirribilli Neighbourhood Centre where Jasper held his first ever show (it was cars in paris, charcoal on paper), and at one time Jasper, myself and Oliver Watts all lived in houses a few hundred metres apart, each with a palm tree in the yard.

There are other, deeper influences beyond this primal imprinting, relationships between place and palette and form that predate childhood. Though the shoreline between Berry Island and Taronga Zoo is now thought of as a wankers’ paradise made boring by real estate, it was for a long time some of the most artistically productive territory in Australia. It incubated movements as well as individual practitioners, including two major two artists’ colonies, first the Curlew Camp at Sirius Cove in the 1890s, and then a series of shared houses around Lavender Bay in the 1970s. Lavender Bay was, then a location so Bohemian with actors, writers and artists that it attracted the pejorative nickname “Poofters’ Hollow”.

Together these zones of influence fostered Arthur Streeton, Tom Roberts, Brett Whiteley, Peter Kingston, Garry Shead, Martin Sharp, Philip Cox, Tim Storrier, and Tom Carment. The same area housed Norman Lindsay, May Gibbs, Lloyd Reeds and Margaret Preston, and was painted many times by Charles Condor, Conrad Martens, Grace Cossington-Smith and Margaret Olley. Olley’s final painting, a triptych in tribute named Sydney Harbour, late afternoon, was painted on recurrent, emphysemic visits to Barry Humphries’ apartment balcony, and it takes in the view across Fort Denison to Cremorne Point and Mosman (once called “Australia’s most painted suburb”) and beyond. Before them, it was the land of countless unknown Gamaragal artists, some of whom left their work carved or stencilled onto the rocks of Balls Head.

After the works in FIREWORKS were completed, someone showed Jasper a print entitled (The Orange) Fruit Dove in Clark Park, also of Sydney palm trees, also in blue. Above them is a cadmium orange bird in flight, and the aspect is unusual. It is the inverse of our usual view of a palm tree – instead of looking up, it looks down through the tree’s crown, the view of a bird coming in to land. The avian flightpath is described by a curled orange parabola. In the middle distance, compressed onto a near horizon, is the Harbour Bridge. This work depicts a view recognisable from the windows of Number One Walker Street, Lavender Bay – the Whiteley House.

Brett and Wendy Whiteley lived together in many palm-rich places. They lived in Fiji, in Bali, and in Tangier, and Brett made art of palms in each. There are even palms visible in his views of Surry Hills, the suburb where he founded his late-career studio. Wendy Whiteley thought it was natural for artists to be drawn to palms because their shape was so sculptural, and Brett made sculptures, both of them (Free standing ultramarine Palm trees) and sculptures from them: Pelican II started with the curl of a fallen palm frond. Palmsm appear all over his paintings, prints, sketches and sometimes pottery designs. He captures them outright and glimpsed out of windows; other times they grow out of works within works.

Most of all, he studied the palms closest to home. The rank of Phoenix canariensis in Clark Park is one of two distinct sets of palms visible from the window of Number One Walker Street. The other is a trio of tall Cabbage Tree Palms that abutt the sky next to Lavender Bay wharf. They were there when the Whiteleys moved in, and became some of the most painted trees in Australian art, a subject for several Lavender Bay artists but most of all Brett, who painted them again and again. These long, foregrounded shapes are persistent in his views of the har- bour, in blue and livid orange and their transpositions. Organic but architectural, they are as distinctive as a signature.

There is now a third grouping of palms that can be seen from Number One Walker Street: it is the stand of Bangalow Palms at the heart of Wendy Whiteley’s garden, which grew from seeds brought south by Arkie Whiteley, their daughter. The seeds thrived, growing into a congregation of cool grey trunks. When Sydney’s original town planners and “town beautifiers” called early plantings of palms “successful”, it meant not only that were aesthetically adjusted. But also that they hadn’t died. They had survived in soil that could punish flowerbed European ideas of civic beauty, and achieved continuity.

FIREWORKS is the fruit of that kind of continuity as well, elements seeded in the unconscious, and then hothoused through experience and practice. It demonstrates not a line of influence that runs from Whiteley to Knight (two very different artists), but a shared influence, the generative, enduring sway of Sydney Harbour and its foreshore, its colour and its shapes, its traffic and its weather. These are paintings that meld two traditions, one personal, and one cultural. So far there is no obvious successor to either. Both the works and the artist are the product of an artistic microclimate that, though endangered, is still lush.

Richard Cooke, 2022